Research Article

Volume 3, Issue 5

Psychosocial Impact of COVID-19 on Occupants in Nigeria

Oluchi A Olofin1 ; Adeniran J Ikuesan2 ; Benneth M Okike3 ; Abdulrasheed M Bello2 ; Eze E Ajaegbu4*; Ijeoma O Okolo2 ; Nnyeneime U Bassey2 ; Tunde A Aduloju2 ; Ukachukwu C Ezeh2 ; Blessing C Nwaso2 ; Flora N Ezugworie2 ; Phina C Ezeagwu2 ; Juliet O Nwigwe2 ; Ethel E Adimora2 ; Juliana O Ndubuisi2 ; Chinenye A Nwobodo2 ; Gloria T Onah5 ; Jane I Ugochukwu6 ; Jennifer N Ewa-Elechi2 ; Florence O Nduka2

1Dental Therapy Department, Federal College of Dental Technology and Therapy, Enugu, Nigeria.

2Applied Sciences Department, Federal College of Dental Technology and Therapy, Enugu, Nigeria.

3Dental Technology Department, Federal College of Dental Technology and Therapy, Enugu, Nigeria.

4Department of Pharmaceutical and Medicinal Chemistry, David Umahi Federal University of Health Sciences, Uburu, Nigeria.

5Science Laboratory Technology, Institute of Management and Technology, Enugu, Nigeria.

6Department of Pharmaceutical Microbiology and Biotechnology, Enugu State University of Science and Technology, Agbani, Nigeria.

Corresponding Author :

Eze E Ajaegbu

Email: ajaegbuee@yahoo.com

Received : Apr 13, 2024 Accepted : May 10, 2024 Published : May 17, 2024 Archived : www.meddiscoveries.org

Citation: Olofin OA, Ikuesan AJ, Okike BM, Bello AM, Ajaegbu EE, et al. Psychosocial Impact of COVID-19 on Occupants in Nigeria. Med Discoveries. 2024; 3(5): 1155.

Copyright: © 2024 Ajaegbu EE. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Background: The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) known as Covid-19 is a public health problem of global significance and a threat to psychosocial alterations. This study aimed to reveal the psychosocial effect of the covid-19 occurrence in Nigeria.

Methods: 1335 participants were collected using a cross-sectional Google online survey. These respondents are those carrying out day to day activities. To pinpoint variables linked to stress changes, a straightforward percentage was utilized.

Results: Out of the 1335 respondents, 22.8%-37.8%, experienced hunger, the outcome of fear of infection & outcome, financial insecurity, fear, set back on personal development, depression, and levels of anxiety. Age below 15 years 1.9%, age 15 to 34 years 63.1%, 19.4% and 17.4% reside in Enugu and Kogi. 48.8% were male. 16.3% were civil servants. 58% had tertiary education, 33.6% earned below 25,000 naira, majority experienced hunger, the outcome of fear of infection, financial insecurity, fear, set back on personal development, depression, levels of anxiety, and others are deprivation of medical health check-up, set-back on personal development, fear, anxiety, panic, stigmatization, loneliness, violence, guilt, difficulties in accessing health facilities, self-medication, job insecurity, impact on educational programs, stress, impact on academic progression, feeling of exhaustion due to work pressure, trauma, overwhelming work pressure, deprivation of education programs, irritability, rape.

Conclusion: This study shows there are various psychosocial factors experienced during the COVID-19 outbreak that varies from individual and various measures should be put in place to reduce these factors.

Keywords: COVID-19; Psychosocial; Syndrome outbreak; Infection; Stigmatization; Fear.

Introduction

Covid-19 is a coronavirus that causes severe acute respiratory syndrome 2(SARS-CoV-2); is a contiguous disease and a major outbreak following the spread of infection of SARSCoV-1 in the year 2002. When the first confirmed case of COVID-19 was identified in December 2019 in the city of Wuhan, the World Health Organization declared the virus a public health emergency of international concern in January 2020, and it was later dubbed a pandemic, the history of the virus cannot be forgotten or overemphasized [1,2].

The COVID-19 have confirmed on the 4th May 2021 to have affected about one hundred fifty four million- two hundred and twelve thousand six hundred and eighty six (154,212,686) people globally and more than three million two-hundred and twenty seven thousand eight hundred and twenty eight (3,227,828) are dead due to this world pandemic outbreak of Corona virus [3]. The Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) have confirmed as at 4th of May 2021 that 165181 number of people have been affected with the contagious virus and 2063 are dead because of this outbreak of coronavirus [4]. The psychological effects of infectious illness outbreaks, such as those caused by SARS and equine influenza, are significant [5-7].

In order to prevent the spread of the contagious virus, the World Health Organization (WHO) has issued several recommendations for a quarantine policy. As a result, more than onethird of the world’s population is currently isolated in some way, which may involve keeping a physical distance of up to 2 meters from people or refraining from attending large mass gatherings [8].

COVID-19 has induced several burdens on many individuals and the globe aside adverse health related problems, which are turning dimensions for instance as social, psychological, and economic. The outbreak of Covid-19 has posed many psychosocial challenges for individuals seeking their day to day activities, governments, scientists, medical community [9-11].

Several studies and surveys have proven that outbreak disease impacts on psychosocial through several ways such as anxiety [12]. In addition, this impact can affect individuals carrying out their everyday coming in contact with other people which will make many losing their jobs and disrupt many businesses and moreover, countries trading with another will be impacted thereby making interconnectivity to exist in modern economies that will make an epidemic to affect international supply chains [13-15]. It was estimated that lost of income in 1918 pandemic experienced US$500 billion per year, which is equivalent to about 0.6% of global income and that the present pandemics can cause total value of losses it the psychosocial factor not attended with [16].

The majority of the research into this outbreak is on how to cope with the transmission, control, and clinical traits of infected people, [17,18] the genetic description of the virus, and demanding for general health control [19]. However, no studies have looked into how COVID-19 has affected Nigeria’s general populace psychosocially.

Therefore, this present study represents the first psychosocial effect and mental health survey conducted in the general population in Nigeria between August to October 2020. This study aimed to reveal the psychosocial impact of the covid-19 outbreak in Nigeria and identify risk and protective factors contributing to psychosocial. This may assist individuals, healthcare workers and many government parastatals in safeguarding the psychosocial wellbeing of the community during the period of the COVID-19 outbreak in Nigeria and world at large.

Materials and methods

Study area

The study area is a giant African country, Nigeria. Nigeria is among one of the countries on Africa’s west coast and occupies 923,768 km2 of land that shared border with Benin, Chad, Niger, and Cameroon [20]. The country is the most densely populated country in African with over 200 million people and comprises of 250 ethnic groups. The three major native languages are Yoruba, Igbo and Hausa with official language is British English [21].

Research design

In order to determine the degree and influence COVID-19 have had on the psychosocial behavior of residents living in Nigeria, data from participants were collected and analyzed. This revealed several potential risk and protective factors contributing to psychosocial imbalances.

Study population and sampling technique

The study was piloted for all occupants carrying out day-today activities living in Nigeria. The sample size for the experiment was 1335 participants across the 37 state of Federal republic of Nigeria. Cross-sectional Google online survey method was used and all participants were occupants residing in the country.

Instrument of data collection

Data for the survey were gathered using a well-designed research questionnaire with the title “Questionnaire on Psychosocial Impact on COVID-19 Analysis in Nigeria.” There are two closed-ended sections to the questionnaire. Section A contains information about the participants’ age, state of origin, gender, occupation, education level, religion, marital status, and monthly income. Section B investigated on the psychosocial impact on the participants about the outbreak of COVID-19.

Method of data collection

The Google online questionnaire was circulated to the occupants across the 37 states in Nigeria due to pandemic lockdown, restriction of movement and physical distancing preventive measure setup by the Nigerian government. The distribution of the questionnaire lasted for 3 months.

Method of data analysis

The data were collected, and to analyze the data, IBM SPSS version 23 was utilized. Descriptive statistics and a straightforward percentage distribution table were then used to discover the factors connected to the psychological changes.

Results

The results were presented using figures and tables for the analysis of psychosocial impact of COVID-19 on respondents.

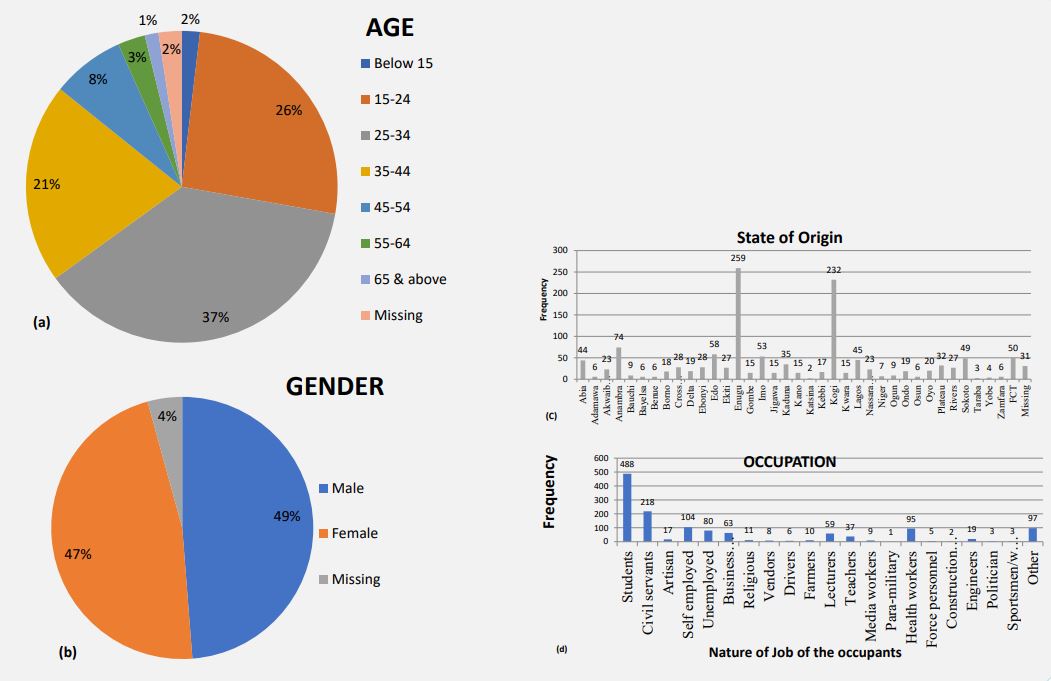

Figure 1a–d shows details regarding the participants’ demographic characteristics. The age of participants were revealed out of 1335 respondent 497(37%) were 25-34 years old, 346(25.9%) were 15-24 years, 277(20.8%) 35-44 old, 101(7.6%) 45-54 old, 38(2.8%) 55-64 years, 25(1.9%) were below 15 years old, while 19(1.4%) 65 and above, and 32(2.4%) were undecided in Figure 1a.

Majority of the respondents were male with frequency of 651(48.8%) while 627(47.0%) female and 57(4.3%) were unknown Figure 1b.

The majority lived in Enugu 259(19.4%), Kogi 232(17.4%), Anambra 74(5.5%), Edo 58(4.4%), Imo 53(4.0%), FCT 50(3.7%), Sokoto 49(3.7%), Lagos 45(3.4%), Abia 44(3.3%), Kaduna 35(2.6%), Plateau 32(2.4%), Cross river 28(2.1%), Ebonyi 28(2.1%), Rivers 27(2.0%), Ekiti 27(2.0%), Akwaibom and Nassarawa were 23(1.7%) each, Oyo 20(1.5%), Delta and Ondo were 19(1.4%) each, Borno 18(1.3%), Kebbi 17(1.3%), Gombe, Jigawa, Kano, Kwara were 15(1.1%) each, , Bauchi, Ogun were 9(0.7%) each, Niger 7(0.5%), Adamawa, Bayelsa Benue, Osun, and Zamfara were 06(0.5%) each, Yobe 04(0.3%), Taraba 3(0.2%), Katsina 2(0.1%) and 31(2.3%) were unknown Figure 1c.

About one-thirds of the participants were students (36.6%, 488/1335), civil servants 218(16.3%), self-employed 104(7.8%), health workers 95(7.1%), unemployed 80(6.0%), business men/ women 63(4.7%), lecturers 59(4.4%), teachers 37(2.8%), engineers 19(1.4%), artisan 17(1.3%), religious leader 11(0.8%), farmers 10(0.7%), media workers 9(0.7), vendors 08(0.6%), drivers 6(0.4%), force personnel 5(0.4%), politician 3(0.2%), sportsmen/women 3(0.2%), construction workers 2(0.2%), para-military 1(0.1%) and other 97(7.3%) Figure 1d.

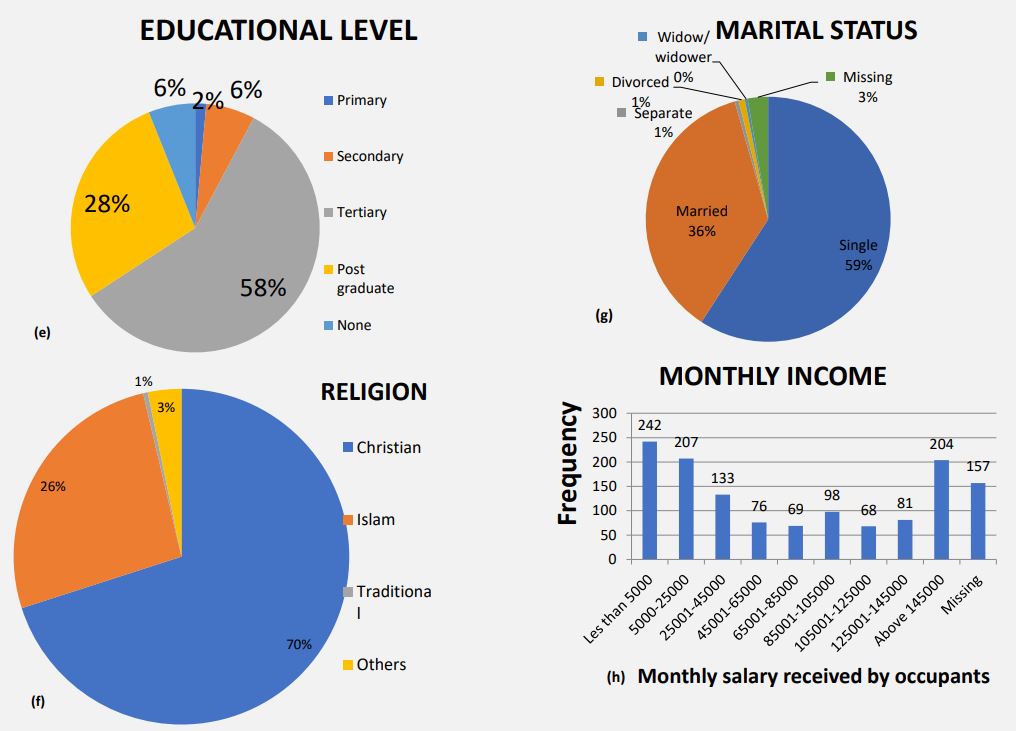

More one half of the respondents had Tertiary and post graduate qualifications 774(58.0%) and 376(28.1%), respectively, while those that went through secondary school 85(6.4%), leaving school certificate 19(1.4%) and 81(6.1%) were unknown in Figure 1e.

Out of 1335 of the participants 935(70.0%) were Christian, while 351(26.3%) were Islam, traditional believer were 06(0.5%) and other religions were found to be 43(3.2%) in Figure 1f.

Most of the respondents were single 790(59.2%), while married 486(36.4%), divorced 11(0.8%), separate 7(0.5%), widow/ widower 05(0.4%) and were unknown 36(2.7%) in Figure 1g.

Majority of the respondents were on receiving monthly salary of less than five thousand naira 242(18.1%), 207(15.5%) were receiving 5000-25000 naira, 133(10.0%) received 25001-45000 naira, 204(15.3%) earned above 145000 naira, 98(7.3%) were paid 85001-105000 naira, 81(6.1%) collected 125001-145000 naira, 76(5.7%) received 45001-65000 naira, 69(5.2%) were paid 65001-85000 naira, 68(5.1%) were collecting 105001- 125000 naira as monthly income salary, and 157(11.7%) were found missing in Figure 1h.

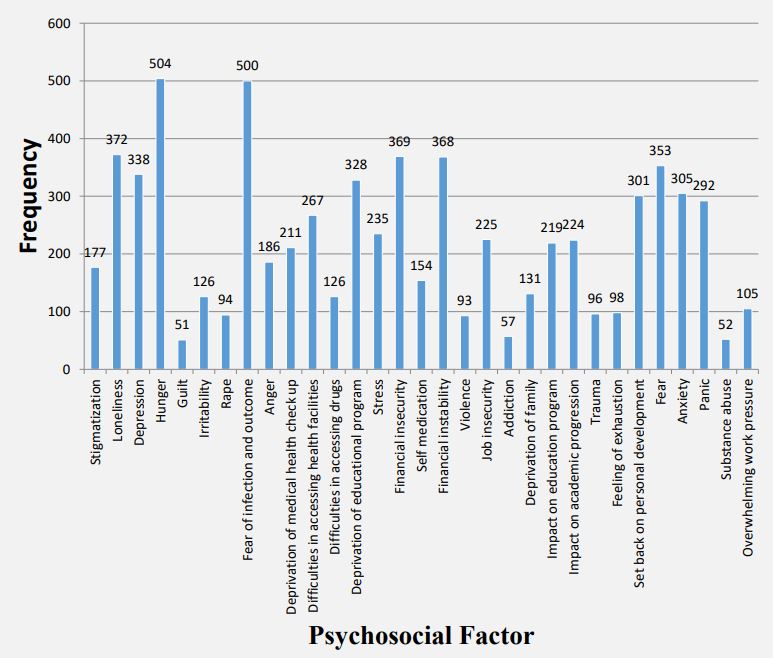

Multiple responses on psychosocial factors on occupants were revealed and majority of the participants affirmed that hunger were most prevalent 504(37.8%) compared to fear of infection and outcome 500(37.5%), loneliness 372(27.9%), financial insecurity 369(27.6%), financial instability 368(27.6%), fear 353(26.4%), depression 338(25.3%), deprivation of educational program 328(24.6%), anxiety 305(22.8%), set back on personal development 301(22.5%), panic 292(21.9%), difficulties in accessing health facilities 267(20.0%), stress 235(17.6%), job insecurity 225(16.9%), impact on academic progression 224(16.8%), impact on education program 219(16.4%), deprivation of medical health check-up 211(15.8%), anger 186(13.9%), stigmatization 177(13.3%), self-medication 154(11.6%), deprivation of family 131(9.8%), irritability 126(9.4%), difficulties in accessing drugs 126(9.4%), overwhelming work pressure 105(7.9%), feeling of exhaustion 98(7.3%), trauma 96(7.2%), rape 94(7.0%), violence 93(7.0%), addiction 57(4.3%), substance abuse 52(3.9%) and guilt 51(3.8%).

Table 1: Psychosocial impact experienced by various occupations

| Students | Effects of covid-19 |

|---|---|

| Stigmatization, loneliness, depression, hunger, guilt, irritability, rape, fear of infection & outcome, anger, deprivation of medical check-up, difficulties in accessing health facilities, difficulties in accessing drugs, deprivation of education program, stress, financial insecurity, self-medi- cation, financial instability, violence, job insecurity, deprivation of family, impact on educational program, trauma, set-back on personal devel- opment, fear, anxiety, panic, substance abuse, overwhelming work pressure. |

|

| Civil servants | Effects of COVID-19 |

| Depression, fear of infection & outcome, deprivation of medical health check-up, set-back on personal development, fear, anxiety, panic, stig- matization, loneliness, hunger, guilt, difficulties in accessing health facilities, self medication, job insecurity, impact on educational programs, stress, impact on academic progression, feeling of exhaustion due to work pressure, trauma, overwhelming work pressure, deprivation of education programs, irritability, rape. |

|

| Artisans | Effects of COVID-19 |

| Stigmatization, loneliness, depression, hunger, guilt, irritability, rape, fear of infection & outcome, anger, deprivation of medical check-up, difficulties in accessing health facilities, difficulties in accessing drugs, deprivation of education program, stress, financial insecurity, self-medi- cation, financial instability, violence, job insecurity, addiction, deprivation of family, trauma, feeling of exhaustion, set-back on personal devel- opment, fear, anxiety, panic, substance abuse, overwhelming work pressure, |

|

| Self employed | Effects of COVID-19 |

| Stigmatization, loneliness, depression, hunger, guilt, irritability, rape, fear of infection & outcome, anger, deprivation of medical check-up, dif- ficulties in accessing health facilities, difficulties in accessing drugs, deprivation of education program, stress, financial insecurity, self-medica- tion, financial instability, violence, job insecurity, addiction, deprivation of family, impact on educational program, impact on academic progres- sion, trauma, feeling of exhaustion, set-back on personal development, fear, anxiety, panic, substance abuse, overwhelming work pressure |

|

| Unemployed | Effects of COVID-19 |

| Stigmatization, loneliness, depression, hunger, guilt, irritability, rape, fear of infection & outcome, anger, deprivation of medical check-up, dif- ficulties in accessing health facilities, difficulties in accessing drugs, deprivation of education program, stress, financial insecurity, self-medica- tion, financial instability, violence, job insecurity, addiction, deprivation of family, impact on educational program, impact on academic progres- sion, trauma, feeling of exhaustion, set-back on personal development, fear, anxiety, panic, substance abuse, overwhelming work pressure. |

|

| Businessmen/ women |

Effects of COVID-19 |

| Stigmatization, loneliness, depression, hunger, guilt, irritability, rape, fear of infection & outcome, anger, deprivation of medical check-up, dif- ficulties in accessing health facilities, difficulties in accessing drugs, deprivation of education program, stress, financial insecurity, self-medica- tion, financial instability, violence, job insecurity, addiction, deprivation of family, impact on educational program, impact on academic progres- sion, trauma, feeling of exhaustion, set-back on personal development, fear, anxiety, panic, substance abuse, overwhelming work pressure. |

|

| Religious leaders | Effects of COVID-19 |

| Stigmatization, loneliness, depression, hunger, fear of infection & outcome, anger, deprivation of medical check-up, difficulties in accessing health facilities, difficulties in accessing drugs, deprivation of education program, stress, financial insecurity, self-medication, financial insta- bility, job insecurity, deprivation of family, impact on educational program, impact on academic progression, trauma, feeling of exhaustion, set-back on personal development, fear, anxiety, panic, overwhelming work pressure. |

|

| Health workers | Effects of COVID-19 |

| Stigmatization, loneliness, depression, hunger, guilt, irritability, rape, fear of infection & outcome, anger, deprivation of medical check-up, dif- ficulties in accessing health facilities, difficulties in accessing drugs, deprivation of education program, stress, financial insecurity, self-medica- tion, financial instability, violence, job insecurity, addiction, deprivation of family, impact on educational program, impact on academic progres- sion, trauma, feeling of exhaustion, set-back on personal development, fear, anxiety, panic, substance abuse, overwhelming work pressure. |

|

| Force personnel | Effects of COVID-19 |

| Stigmatization, loneliness, depression, hunger, guilt, irritability, rape, fear of infection & outcome, anger, deprivation of medical check-up, dif- ficulties in accessing health facilities, difficulties in accessing drugs, deprivation of education program, stress, financial insecurity, self-medica- tion, financial instability, violence, job insecurity, addiction, deprivation of family, impact on educational program, impact on academic progres- sion, trauma, feeling of exhaustion, set-back on personal development, fear, anxiety, panic, substance abuse, overwhelming work pressure. |

|

| Vendors | Effects of COVID-19 |

| Hunger, irritability, fear of infection & outcome, anger, deprivation of education program, financial insecurity, financial instability, job insecu- rity, feeling of exhaustion, fear, anxiety, panic, substance abuse, overwhelming work pressure. |

|

| Drivers | Effects of COVID-19 |

| Stigmatization, loneliness, depression, hunger, guilt, irritability, rape, fear of infection & outcome, anger, deprivation of medical check-up, difficulties in accessing health facilities, difficulties in accessing drugs, deprivation of education program, stress, financial insecurity, self-med- ication, financial instability, violence, job insecurity, addiction, deprivation of family, impact on educational program, impact on academic progression, trauma, feeling of exhaustion, set-back on personal development, fear, anxiety, panic, overwhelming work pressure. |

|

| Farmers | Effects of COVID-19 |

| Stigmatization, loneliness, depression, hunger, guilt, irritability, rape, fear of infection & outcome, anger, deprivation of medical check-up, difficulties in accessing health facilities, stress, financial insecurity, self-medication, financial instability, violence, job insecurity, addiction, de- privation of family, impact on educational program, impact on academic progression, trauma, set-back on personal development, fear, anxiety, panic, substance abuse, overwhelming work pressure. |

|

| Lecturers | Effects of COVID-19 |

| Stigmatization, loneliness, depression, hunger, guilt, irritability, rape, fear of infection & outcome, anger, deprivation of medical check-up, dif- ficulties in accessing health facilities, difficulties in accessing drugs, deprivation of education program, stress, financial insecurity, self-medica- tion, financial instability, violence, job insecurity, addiction, deprivation of family, impact on educational program, impact on academic progres- sion, trauma, feeling of exhaustion, set-back on personal development, fear, anxiety, panic, substance abuse, overwhelming work pressure. |

|

| Teachers | Effects of COVID-19 |

| Stigmatization, loneliness, depression, hunger, guilt, irritability, rape, fear of infection & outcome, anger, deprivation of medical check-up, dif- ficulties in accessing health facilities, difficulties in accessing drugs, deprivation of education program, stress, financial insecurity, self-medica- tion, financial instability, violence, job insecurity, addiction, deprivation of family, impact on educational program, impact on academic progres- sion, trauma, feeling of exhaustion, set-back on personal development, fear, anxiety, panic, substance abuse, overwhelming work pressure. |

|

| Media workers | Effects of COVID-19 |

| Loneliness, depression, hunger, irritability, fear of infection & outcome, anger, difficulties in accessing health facilities, stress, financial insecu- rity, financial instability, job insecurity, set-back on personal development, fear, anxiety, panic, overwhelming work pressure. |

|

| Paramilitary | Effects of COVID-19 |

| Stigmatization, loneliness, depression, hunger, guilt, irritability, rape, fear of infection & outcome, anger, deprivation of medical check-up, dif- ficulties in accessing health facilities, difficulties in accessing drugs, deprivation of education program, stress, financial insecurity, self-medica- tion, financial instability, violence, job insecurity, addiction, deprivation of family, impact on educational program, impact on academic progres- sion, trauma, feeling of exhaustion, set-back on personal development, fear, anxiety, panic, substance abuse, overwhelming work pressure. |

|

| Construction workers |

Effects of COVID-19 |

| Fear of infection and outcome, financial insecurity, job insecurity | |

| Engineers | Stigmatization, loneliness, depression, hunger, guilt, irritability, rape, fear of infection & outcome, anger, deprivation of medical check-up, difficulties in accessing health facilities, difficulties in accessing drugs, deprivation of education program, stress, financial insecurity, self-med- ication, financial instability, violence, job insecurity, deprivation of family, impact on educational program, impact on academic progression, trauma, feeling of exhaustion, set-back on personal development, fear, anxiety, panic, substance abuse, overwhelming work pressure. |

| Politicians | Effects of COVID-19 |

| Stigmatization, loneliness, depression, hunger, guilt, irritability, rape, fear of infection & outcome, anger, deprivation of medical check-up, dif- ficulties in accessing health facilities, difficulties in accessing drugs, deprivation of education program, stress, financial insecurity, self-medica- tion, financial instability, violence, job insecurity, addiction, deprivation of family, impact on educational program, impact on academic progres- sion, trauma, feeling of exhaustion, set-back on personal development, fear, anxiety, panic, substance abuse, overwhelming work pressure. |

|

| Sportsmen/ women |

Effects of COVID-19 |

| Stigmatization, loneliness, depression, hunger, guilt, irritability, fear of infection & outcome, anger, difficulties in accessing health facilities, deprivation of education program, stress, financial insecurity, self-medication, financial instability, trauma, feeling of exhaustion, set-back on personal development, fear, anxiety, panic, substance abuse. |

|

| Others | Effects of COVID-19 |

| Stigmatization, loneliness, depression, hunger, guilt, irritability, rape, fear of infection & outcome, anger, deprivation of medical check-up, dif- ficulties in accessing health facilities, difficulties in accessing drugs, deprivation of education program, stress, financial insecurity, self-medica- tion, financial instability, violence, job insecurity, addiction, deprivation of family, impact on educational program, impact on academic progres- sion, trauma, feeling of exhaustion, set-back on personal development, fear, anxiety, panic, substance abuse, overwhelming work pressure. |

Table 1 explained psychosocial impact experienced by various occupations, it was examined that stigmatization, loneliness, depression, hunger, guilt, irritability, rape, fear of infection & outcome, anger, deprivation of medical check-up, difficulties in accessing health facilities, difficulties in accessing drugs, deprivation of education program, stress, financial insecurity, self-medication, financial instability, violence, job insecurity, addiction, deprivation of family, impact on educational program, impact on academic progression, trauma, feeling of exhaustion, set-back on personal development, fear, anxiety, panic, substance abuse, overwhelming work pressure were experienced during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Discussion

This study tried to ascertain the psychosocial factors on occupants in Nigeria as a result of COVID-19 irruption and its effect on various occupations. Out of the 1335 respondents, 22.8%-37.8%, experienced hunger, the outcome of fear of infection & outcome, financial insecurity, fear, set back on personal development, depression, and levels of anxiety. Age below 15 years 1.9%, age 15 to 34 years 63.1%, 19.4% and 17.4% reside in Enugu and Kogi. 48.8% were male. 16.3% were civil servants. 58% had tertiary education, 33.6% earned below 25,000 naira.

More than one-third of the respondents evinced hunger and fear of the outcome of infection, while one-fifth had loneliness, financial insecurity, financial instability, fear, depression, deprivation of educational program, anxiety, set back on personal development, panic, and difficulties in accessing health facilities. One-ten of the participants had a minor on stress, job insecurity, impact on academic progression, impact on the education program, deprivation of medical health check-up, anger, stigmatization, self-medication and less than one-ten respondents had COVID-19 related deprivation of family, irritability, difficulties in accessing drugs, overwhelming work pressure, feeling of exhaustion, trauma, rape, violence, addiction, substance abuse and guilt.

The present reported 37.8% and 37.5% had a prevalence of hunger and fear of the outcome of infection, respectively. No studies were found as regards hunger on the psychosocial impact this is the first. While the present study indicated that fear of infection was greater than that of Souvik Dubey et al., who consorted that frontline healthcare workers are more endanger of contracting the contagious disease by experiencing adverse psychological outcomes in form of fear of the risk of the infection [22].

The present study affirmed that loneliness, financial insecurity, financial instability, fear, depression, deprivation of educational program, anxiety, set back on personal development, panic, and difficulties in accessing health facilities were moderately high among the occupants in Nigeria. Psychosocial loneliness, in this study, was 27.86%, which was found higher, compared to that of Cuiyan, et al. 2020 reported 15.3% in order to avoid COVID19 made about the COVID-19 outbreak [23]. Among health workers and the quarantine population, an increase has been observed in the number of people in isolation and loneliness due to the contagious disease in Wuhan, China [24].

In this present study financial insecurity and financial instability were 27.64% and 27.56%, respectively. Other studies reported similar trends noticed a moderate increase in financial insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic that led to an increase of worker disengagement overtime in their job [24]. Economic difficulties bring about financial instability, chronic stress circumstances in families generating distress about their thoughts contributes to fear, anxiety and making occupants neglecting the current standard of living [25,26].

The present inquiry showed 26.44%, 21.87%, 25.31% prevalence of fear, panic and depression of COVID-19, respectively. These prevalence values enormously lower ≥66% for fear, ≥83% for panic and greatly higher ≤13% reported in other researches. The spontaneous contagion of fear and panic through social media could fuel psychosocial reactions in midst of crises and might transfer the disease to the family members that bring about unnecessary worry about the COVID-19 outbreak [23,28- 31].

It was revealed that 24.56% had deprivation during their educational program this was asserted by Edeh al. Zamira and Linda that the COVID-19 pandemic has devastating effects on the educational programs and a number of obstacles might prevent teachers and students from participating in online education for continuing learning during the COVID-19 lockout [32,33]. This is also consistent with the analysis of the COVID-19 pandemic’s effects on education funding, which revealed evidence of the pandemic’s likely detrimental effects on those funds [34].

The level of anxiety in this study was 22.8% found higher with research carried out in other countries 13.9%-46%. Most of the time workers feeling too much unnecessary worry about the COVID-19 outbreak [23,30,35,36].

Set back on personal development 22.55%. Some effects of the coronavirus pandemic were likely to be long-lasting, including lower spendable income for young adults, altered skill development as a result of school closures, damaged careers, coronavirus-related changes in our societal context (resources/ affordances) and societal changes in risk perception, which in turn might affect normative shifts and developmental continuities [37,38].

The current study found that 20% of people had trouble getting to medical facilities, which is consistent with research on how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected access to healthcare in Low- and Middle-Income Nations (LMICs), numerous viable techniques can be implemented to ensure that the provision of healthcare is not interrupted. Medical personnel suggested that the work setting was yet to be equipped which will be adequate by supplying PPE [31,39].

This study showed that stress, job insecurity, impact on academic progression, impact on the education program, deprivation of medical health check-up, anger, stigmatization, and selfmedication had a moderately low.

Stress in this present study is higher compared with previous research conducted Ming yu et al., 8.6%, and Sarah et al., confirmed that stress was present, with a low-stress group exhibiting the opposite trend and a high-stress group exhibiting an increase in psychopathological symptoms and a loss in feeling of coherence [30,40].

The present inquiry showed a 16.85% prevalence of job insecurity of COVID-19. Wanberg, et al. 2012 projected that there will be an increase in job insecurity as many industries such as hospitality, travel, entertainment and sports were locked down that tens of millions of individuals in the entire U.S filed new unemployment claims in early 2020 as an issue of contagious COVID-19. Job insecurity can cause stress-related outcomes such as depression, anxiety, and physical ailments [41]. Resilience among employees’ personal resources serves as a bulwark against the devastation caused by perceived job instability [42].

The impact on education program and impact on academic progression in this study was 16.02%, and 16.78%, respectively and previous research has demonstrated that children cannot learn well at home, rendering the online learning system inefficient. A high level of dissatisfaction on diminishing academic performance was noted during online learning and students who lived alone during the isolation were more prone to depression during online learning [43,44].

This present study reported 15.80% and 11.53%, had a prevalence of deprivation of medical health check-ups and selfmedication, respectively. A medical checkup is lower with other researches 20.3-23.9% and this could be due to a high level of fear and without observing the contagious COVID-19 disease in a large number of participants, panic that leads people to self-medicate could also be brought on by a sense of insecurity influenced by the accessibility of local medical resources, the effectiveness of the public health system, and the prevention and control measures implemented in the pandemic situation [36,45].

The level of anger in this study was 13.93% and is in line with research conducted by Radek and Radmila, 2020 which indicated 16% of anger [46].

This current research showed that stigmatization experienced by the occupants was 13.25%. Stigmatization is in fact repeated responses in the consequence of emergencies of all kinds, including disasters, acts of terrorism, and preceding pandemics [47]. Some African residents of Guangzhou, China, reportedly experienced shame due of the amount of presumption surrounding COVID-19 infectors, according to a recent news story on the disease. Although COVID-19 is a virus that might potentially lead to life-threatening illnesses, it is not a death sentence in and of itself. Nevertheless, people often stigmatize those who have COVID-19 out of fear, prejudice, and/or ignorance [47-49].

The study revealed that deprivation of family, irritability, overwhelming work pressure, feeling of exhaustion, trauma, rape, violence, addiction, substance abuse and guilt had a minor COVID-19 related psychosocial impact.

This study showed that deprivation of family was 9.81%. This In line with research conducted by Fernando et al., the majority of participants ranging 57.8-77.9% experienced increased support, shared feeling and care from family members and others [50,51].

According to this study, 26.44% of Nigerian residents had a significantly higher fear of COVID-19 because to their psychological symptoms of high irritability and poor sleep quality. Extreme fear negatively impacts a person’s psychological health, which can result in irritation, poor sleep quality, and irrational sensations of anxiety [52].

The overwhelming work pressure in this study was 7.87%. The medical care workers experienced an overwhelming workload, lack of necessary medical supplies, numerous threats plus stigmatization, and danger of being diseased or contaminating others [30].

Fatigue is used not in any clinical or diagnostic sense, instead of it is used in daily language to refer to exhaustion, tiredness, a feeling of being worn out [53]. This study examined a prevalence of 7.34% of the feeling of exhaustion. Wang et al., 2020 often reported clinical signs and symptoms at the beginning of fatigue (11%-44%), (Ebru et al., 2020) reported 64.1% of participants were categorized as psychologically fatigued [54,55].

The present finding showed that 7.19% had traumatic stress 19 is associated with psychosocial manifestations of COVID-19 contagious disease. This is lower when compared with previous studies that supported the traumatic stress was 15.2-18.4% [36]. Due to the possibility of conceptualizing the COVID-19 pandemic as a traumatic event, psychosocial support during the pandemic must include a trauma-informed lens, which prioritizes emotional safety, places an emphasis on collaboration, choice, and transparency, gives people’s lived experiences priority, and aims to prevent re-traumatization [56]. Healthcare workers have a greater risk of acquiring post-traumatic stress disorder and burnout; thus, it is important to understand on how to prevent, identify, and manage such problems [57].

Occupants witnessed 7.04% of rape cases this was asserted by WHO, 2017 that reported 35% of women have experienced physical or sexual assault by a romantic relationship or by someone other than a spouse at some point in their lives [58]. Franklin and Menakar; 2016, proposed that individual differences in everyday behaviors may increase or decrease the likelihood that someone will be seen as vulnerable and chosen as a target [59]. According to the United Nations Population Fund, domestic and sexual violence have likely grown globally as a result of the ongoing COVID-19 epidemic [60].

This study showed that 6.96% confirmed the rate of violence as a result of COVID-19 related disease. In comparison with (ICRC; 2020) that reported overall 41.9% violence between two months. Verbal, being unjustly accused, being stigmatized, physical aggression, being threatened, causing damage to the facility, and being shown a weapon were among the more frequent forms of violence experienced. The misconception that COVID-19 was a manufactured conspiracy and that people were being tested and admitted without a need was a key contributor to the violence, which was propagated on social media [61]. Healthcare professionals have noted that there is a heightened danger of violence in drug and alcohol rehabilitation centers. Being safe and secure in terms of one’s physical and mental health is a fundamental right for all service providers, whether they are members of a peer group or a professional service provider [62].

The addiction of drug and substance abuse in this study was 4.26% and 3.89%, respective. According to previous research, drug users are typically a stigmatized, disadvantaged group with limited access to healthcare. They experience worse health, impaired immunological response, persistent infections, different problems with the cardiovascular, pulmonary, and metabolic systems, as well as a variety of psychological comorbidities [63,64]. According to Simona et al., drug users may turn to alternative psychotropic medications through illicit internet marketplaces as a result of their increased psychological discomfort brought on by social isolation and the likely limited access to detoxification facilities. A global summary of the emerging drug addiction patterns during the ongoing COVID-19 epidemic [65].

This study showed that 3.82% confirmed Guilt. (Cândea and Szentagotai-Tˇata, 2018), reported that shame and guilt are in many ways connected to severe psychological symptoms that can pose a serious threat to mental health when they are not effectively understood and controlled [66]. The functioning of shame and guilt is examined in the current research along with their connections to the pandemic crisis. Susan and Daniel raised the potential that those social workers would feel terrible if they unintentionally or carelessly caused someone else to develop the sickness [67].

Conclusion

This study shows there are various psychosocial factors experienced during the COVID-19 outbreak that varies from individual and various measures should be put in place to reduce these factors.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval to carry out the research work was obtained from the Institutional Review Committee of the Federal College of Dental Technology and Therapy, Nigeria. All participants gave their informed consent before inclusion in this study, and their confidentiality was preserved.

Consent for publication: The authors give their consent for publication.

Availability of data and materials: The data can be obtained by reaching out to the corresponding author upon request.

Competing interests: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

EthicalFunding sources: This work received no support from any funding agency.

Author contributions

EEA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - original draft, Formal analysis, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Software, Supervision. OAO, AJI, BMO, AMB, IOO, NUB, TAA, UCE, BCN, FNE, PCE, JON, JON, CAN, GTO, JIU, JNE, FON: Funding acquisition, Validation, formal analysis, and data curation.

Acknowledgement:Not applicable.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Pneumonia of Unknown Cause-China. Emergencies Preparedness, Response. Disease Outbreak News. 2020. https://www.who.int/csr/don/05-january-2020-pneumonia-ofunkown-cause-china/en/.

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19. 2020. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/whodirector-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-oncovid-19---11-march-2020.

- United Nations Geoscheme (UN). Reported Cases and Deaths by Country or Territory on COVID-19. 2021. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/.

- Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC). (2021). COVID-19 Nigeria. 2021. https://covid19.ncdc.gov.ng/.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Infection prevention and control of epidemic- and pandemic-prone acute respiratory infections in health care. Published. 2014. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/112656/9789241507134_eng.pdf.

- Eskild Petersen, Marion Koopmans, Unyeong Go, Davidson H Hamer, et al. Comparing SARS-CoV-2 with SARS-CoV and influenza pandemics. Personal view. 2020; 20(9): E238-E244.

- Events Alexander Rozenta, Anders Kottorp, Johanna Boettcher, Gerhard Andersson, Per Carlbring. Negative Effects of Psychological Treatments: An Exploratory Factor Analysis of the Negative Effects Questionnaire for Monitoring and Reporting Adverse and Unwanted. PLoS ONE. 2016; 11(6): 1-23.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global strategies for controlling infectious diseases advise against placing. Chapter 10: Controlling the spread of infectious diseases. Advancing the right to health: The vital role of law. 2012; 205: 358-65. https://www.who.int/healthsystems/topics/health-law/chapter10.pdf.

- Jörg M Fegert, Benedetto Vitiello, Paul L Plener, Vera Clemens. Challenges and burden of the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: A narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. 2020; 14: 20.

- Julio Garcia, Geoffrey L Cohen. A Social Psychological Perspective on Educational Intervention. Chapter prepared for E. Shafir (Ed.), The Behavioral Foundations of Policy. 2013.

- Sheela Sundarasen, Karuthan Chinna, Kamilah Kamaludin, Mohammad Nurunnabi, Gul Mohammad Baloch, et al. Psychological Impact of COVID-19 and Lockdown among University Students in Malaysia: Implications and Policy Recommendations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020; 17: 6206.

- Chunhong Shi, Zhihua Guo, Chan Luo, Changbin Lei, Pan Li. The Psychological Impact and Associated Factors of COVID-19 on the General Public in Hunan, China. DovePress Journal on Risk Management and Healthcare Policy. 2020: 13.

- Delivorias A, Scholz N. Economic impact of epidemics and pandemics. Eur Parliam Res Serv. 2020; PE646(195): 1‑10.

- Anthony Powell, Temporary Kings: A Novel, Heinemann: CONSEQUENCES OF UNEMPLOYMENT. 1973; 3: 2. www.aphref.aph.gov.au_house_committee_ewr_owk_report_chapter2.pdf.

- United Nations, Geneva. Impact of the Pandemic on Trade and Development Transitioning To a New Normal. 2020. https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/osg2020d1_en.pdf.

- World Health Organization Geneva. Sixth report on the world health situation 1973-1977 Part I: Global analysis. 1980. h t t p : / / a p p s . w h o . i n t / i r i s / b i t s t r e a m / h a n -dle/10665/44199/9241580046_part1_eng.pdf;jsessionid=A4AFB18ABFA0DF773D88682BF962A316?sequence=1.

- WHO. Outbreak Communication; Best practices for communicating with the public during an outbreak. 2004. https://www.afro.who.int/sites/default/files/2017-06/outbreak_com_best_practices.pdf.

- W Guan, Z Ni, Yu Hu, W Liang, C Ou, et al. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020; 382(18).

- Ayman MAl-Qaanehab, ThamerAlshammaria, Razan Aldahhana, HananAldossaryac, Zahra Abduljaleel Alkhalifaha, et al. Genome composition and genetic characterization of SARS-CoV-2. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences. 2021; 28(3): 1978-1989.

- Ekiti State Government. History of Ekiti State. 2020. http://ekitistate.gov.ng.2016.20.

- National Population Commission, Nigeria. Population and Housing Census of the Federal Republic of Nigeria: National and State Population and Housing Tables, Priority Tables. 2006; 1. https://www.scirp.org. 20.

- Souvik Dubey, Payel Biswas, Ritwik Ghosh, Subhankar Chatterjee, Mahua Jana Dubey, et al. Psychosocial impact of COVID-19. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews. 2020; 14: 779-788.

- Cuiyan Wang, Riyu Pan, Xiaoyang Wan, Yilin Tan, Linkang Xu, et al. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17: 1729-1754.

- Debanjan Banerjee, Mayank Rai. Social isolation in Covid-19: The impact of loneliness. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2020; 1-3.

- Roziah Mohd Rasdi, Zeinab Zaremohzzabieh, Seyedali Ahrari. Financial Insecurity during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Spillover Effects on Burnout-Disengagement Relationships and Performance of Employees Who Moonlight. Journal of Frontiers in Psychology. 2021; 12: 610138.

- Marjanovic Z, Greenglass ER, Fiksenbaum L, De Witte H, GarciaSantos F, et al. Evaluation of the Financial Threat Scale (FTS) in four European, non-586 student samples. J Behav Exp Econo. 2015; 55: 72-80.

- Fiksenbaum L, Marjanovic Z, Greenglass E. Financial threat and individuals’ willingness to 581 change financial behavior. R Behav Finan. 2017; 9: 128-147.

- King Costa. The Cause of Panic at the Outbreak of COVID-19 in South Africa - A Comparative Analysis with Similar Outbreak in China and New York. 2020. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339834946.

- Janni Leung, Jack Yiu, Chak Chung, Calvert Tisdale, Vivian Chiu, et al. Anxiety and Panic Buying Behaviour during COVID-19 Pandemic-A Qualitative Analysis of Toilet Paper Hoarding Contents on Twitter. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18: 1127. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18031127.

- Ming-Yu Si, Xiao-You Su, Yu Jiang, Wen-Jun Wang, Xiao-Fen Gu, et al. Psychological impact of COVID-19 on medical care workers in China. Journal of Infectious Diseases of Poverty. 2020; 9: 113.

- Sanaa M Taghaddom, Heyam MARB, Alrashidi, Hoda Diab Mohamed, Marthal Nandhini Johnson. The Impact of Coronavirus on Staff Nurses Feeling While Giving Direct Care to COVID-19 Patients in Various COVID Facilities. Journal of Nursing. 2020; 10: 873-889.

- Edeh Michael Onyema, Nwafor Chika Eucheria, Faith Ayobamidele Obafemi, Shuvro Sen, Fyneface Grace Atonye, et al. Impact of Coronavirus Pandemic on Education. Journal of Education and Practice. 2020; 11(13).

- Zamira Hyseni Duraku, Linda Hoxha. The impact of COVID-19 on education and on the well-being of teachers, parents, and students: Challenges related to remote (online) learning and opportunities for advancing the quality of education. 2020. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341297812.

- World Bank. World Development Report 2018: The Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Education Financing. Washington D.C., World Bank. 2020.

- Gabriele Saccone, Alessia Florio, Federica Aiello MD, Roberta Venturella, Maria Chiara De Angelis, et al. Psychological impact of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnant women. AUGUST 2020 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2020; 293.

- Mark Shevlin, Orla McBride, Jamie Murphy, Jilly Gibson Miller, Todd K Hartman, Liat Levita, et al. Depression, Traumatic Stress, and COVID-19 Related Anxiety in the UK General Population During the COVID-19 Pandemic. BJPsych Open. 2020; 6: e125. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2020.10.

- World Bank (2021). Skills development in the time of COVID-19: Taking stock of the initial responses in technical and vocational education and training. 2021. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/---ifp_skills/documents/publication/wcms_766557.pdf.

- Gabriella Garcia Moura, Célia Regina Rangel Nascimento, Juliene Madureira Ferreira. COVID-19: Reflections on the Crisis, Transformation, and Interactive Processes under Development. Trends in Psychology. 2021; 29: 375-394.

- Melody Okereke, Nelson Ashinedu Ukor, Yusuff Adebayo Adebisi, Isaac Olushola Ogunkola, Eseosa Favour Iyagbaye, et al. Impact of COVID‐19 on access to healthcare in low‐ and middle‐income countries: Current evidence and future recommendations. International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 2020; 1-5.

- Sarah K Schäfer, M Roxanne Sopp, Christian G Schanz, Marlene Staginnus, Anja S Göritz, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on Public Mental Health and the Buffering Effect of a Sense of Coherence. Journal of Psychother Psychosom. 2020; 89: 386-392.

- Wanberg CR. The individual experience of unemployment. Annual Review of Psychology. 2012; 63: 369-396.

- Hobfoll SE. Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Review of general psychology. 2002; 6(4): 307-324. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.6.4.307.

- Owusu-Fordjour C, Koomson CK, Hanson D. The Impact of Covid-19 on Learning - The Perspective of the Ghanaian Student. European Journal of Education Studies. 2020; 7(3).

- Aidos K Bolatov, Telman Z Seisembekov, Altynay Zh Askarova, Raushan K Baikanova, Dariga S Smailova, et al. Online-Learning due to COVID-19 Improved Mental Health among Medical Students. Medical Science Educator. 2021; 31: 183-192.

- Wind TR, Komproe IH. The mechanism that associate community social capital with post disaster mental health: a multilevel model. Soc Sci Med. 2012; 75: 1715-20.

- Radek Trnka, Radmila Lorencova. Fear, Anger, and Media-Induced Trauma during the Outbreak of COVID-19 in the Czech Republic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2020; 12(5): 546-549.

- White AR. Historical linkages: Epidemic threat, economic risk, and xenophobia. The Lancet. 2020.

- BBC. Covid-19 stigma: Chinese hotels & apartments don pursue Africans comot from dia property for fear of coronavirus. 2020. https://www.bbc.com/pidgin/tori-52211995.

- Li T, Lu H, Zhang W. Clinical observation and management of COVID-19 patients. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020; 9(1): 687-690. doi:10.1080/22221751.2020.1741327.

- Fernando Flores Tavares, Gianni Betti. Vulnerability, Poverty and COVID-19: Risk Factors and Deprivations in Brazil. Published in World Development. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105307.

- Yingfei Zhang, Zheng Feei Ma. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health and Quality of Life among Local Residents in Liaoning Province, China: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17: 2381; doi:10.3390/ijerph17072381.

- Janet Alexis A, De Los Santos, Leodoro J Labrague, Charlie C Falguera. Fear of COVID-19, poor quality of sleep, irritability, and intention to quit school among nursing students: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. 2021; 1-8.

- World Health Organization 2020. Pandemic fatigue reinvigorating the public to prevent COVID-19. 2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/335820/WHO-EURO-2020-1160-40906-55390-eng.pdf.

- Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020; 323(11): 1061-9. DOI:10.1001/jama.2020.1585.

- Ebru Morgul, Abdulbari Bener, Muhammed Atak, Salih Akyel, Selman Aktaş, et al. COVID-19 pandemic and psychological fatigue in Turkey. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2020; 1-8.

- Rahbar. Psychosocial Support during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Training Manual for Counsellors. 2021. Available at: Rahbar_NDMA-manual1_compressed1.pdf.

- Sadhika Sood. Psychological effects of the Coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic. RHiME. 2020; 7: 23-6.

- WHO. Violence against women. WHO. 2017. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women.

- Franklin Cortney A, Menaker Tasha A. Feminist Routine Activity Theory and Sexual Assault Victimization: Estimating Risk by Perpetrator Tactic among Sorority Women, Victims & Offenders. 2016. DOI: 10.1080/15564886.2016.1250692.

- UNFPA. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Family Planning and Ending Genderbased Violence, Female Genital Mutilation and Child Marriage. UNFPA. 2020. https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource pdf/COVID19_impact_brief_for_UNFPA_24_April_2020_1.pdf.

- International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). Violence and Stigma Experienced By Health-Care Workers in Covid-19 HealthCare Facilities in Three Cities of Pakistan. 2020.https://www.icrc.org/en/download/file/152026/2020_hcid_covid_violence_report_revised.pdf

- Ali Farhoudian, Alexander Baldacchino, Nicolas Clark, Gilberto Gerra, Hamed Ekhtiari, et al. COVID-19 and Substance Use Disorders: Recommendations to a Comprehensive Healthcare Response. An International Society of Addiction Medicine (ISAM) Practice and Policy Interest Group Position Paper. Basic and Clinical Neuroscience. 2020; 11(2): 129-146.

- Ahern J, Stuber J, Galea S. Stigma, discrimination and the health of illicit drug users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007; 88(2-3): 188-96. (DOI:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.014).

- Stuber J, Galea S, Ahern J, Blaney Sh, Fuller C. (2003). The association between multiple domains of discrimination and self‐assessed health: A multilevel analysis of Latinos and blacks in four low‐income New York City neighborhoods. Health Services Research. 2003; 38(6 Pt 2): 1735-60. DOI:10.1111/ j.1475-6773.2003.00200.x.

- Simona Zaami1, Enrico Marinelli, Maria Rosaria Varì. New Trends of Substance Abuse during COVID-19 Pandemic: An International Perspective. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2020; 11.

- Cândea DM, Szentagotai-Tˇata A. Shame-proneness, guiltproneness and anxiety symptoms: A meta-analysis. J. Anxiety Disord. 2018; 58: 78-106. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.07.005.

- Susan Radcliffe, Daniel Pollack. Put a new tilt on Covid-19 guilt. 2021. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/350121277.