Research article

Volume 2, Issue 3

Difficulties, Problems, Limitations, Challenges, and Corruption Facing Cancer Patients in the Occupied Palestinian Territories: The West Bank, Including East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip

Hilmi S. Salem*

Sustainable Development Research Institute, Bethlehem, West Bank, Palestine.

Corresponding Author :

Hilmi S Salem

Email: hilmisalem@yahoo.com

Received : Jan 07, 2023 Accepted : Mar 10, 2023 Published : Mar 17, 2023 Archived : www.meddiscoveries.org

Citation: Salem HS. Difficulties, Problems, Limitations, Challenges, and Corruption Facing Cancer Patients in the Occupied Palestinian Territories: The West Bank, Including East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip. Med Discoveries. 2023; 2(3): 1024. http://meddiscoveries.org/pdf/1024.pdf

Copyright: © 2023 Salem HS. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

This research was conducted in relation to the cancer status in the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPT): The West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip, with a total population of about 5.4 million and an area of about 6,000 km2. The mortality rate from several types of cancer was 14% in 2016, representing the second cause of death after cardiovascular diseases which account for 30.6% of all causes of death in the OPT. Cancer mortality in the OPT increased by 136% from 2000 to 2016, and by 14% from 2016 to 2020. In addition to other types of cancer in the OPT, its main types are lung (highest in males), breast (highest in females), colorectal (highest in both sexes), and leukemia (highest in adolescents and children). This research paper explains, clearly, honestly, and bravely, in analytical scientific manner, the difficulties, problems, limitations, and challenges facing Palestinian cancer patients in the OPT. It also objectively connects these challenges with the on-going corruption practices that, negatively, influence cancer patients’ access to treatment in a timely manner; thus could influence their survival opportunities. The paper recommends that the OPT’s cancer patients should be treated well, comfortably, humanely, physically, and financially, with due respect for freedom and ease of movement, and without limitations and corruption.

Abbreviations: ANERA: American Near East Refugee Aid; AVH: Augusta Victoria Hospital, East Jerusalem, Occupied Palestine; BJGH: Beit Jala Governmental Hospital (King Hussein Hospital), Beit Jala, OWB; COVID-19 Corona Virus Disease 2019; DPLC: Difficulties, Problems, Limitations, and Challenges; EJHN: East Jerusalem Hospital Network; EU: European Union; FoP: Fear of Progression; HL: Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Cancer; KAHHP: Khaled Al-Hassan Hospital for Cancer and Bone Marrow Transplant Project; MENA: Middle East and North Africa; MoH: Ministry of Health, Ramallah, PA, OPT; NGOs: Nongovernmental Organizations; NHL: Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Cancer; NNUH: An-Najah National University Hospital; OHC: Oncology-Hematology Center; OPT: Occupied Palestinian Territories; OWB: Occupied West Bank; PA: Palestinian Authority; PCRF: Palestine’s Children’s Relief Fund; PECDAR: Palestinian Economic Council for Development and Reconstruction; PH: Palestine Hospital, Harmala, Bethlehem Governorate, OWB; PMC: Palestine Medical Complex, Ramallah, OWB; PTG: Post-Traumatic Growth; UNDP: United Nations Development Programme; UNRWA: United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees; USA: United States of America.

Units: Euro: European Union’s Currency; km2: square kilometers (area unit); m: meter (length unit); m2: meter square (area unit); m3: cubic meter (volume unit); NIS: New Israeli Shekel (the Israeli currency used in the OPT); USD: United States’ Dollar.

Introduction

Worldwide, not much research was undertaken to investigate the difficulties, problems, limitations, and challenges (DPLC) facing cancer patients, and that evaluates the effectiveness of approved interventions, while getting treatment. An increasing number of people are being diagnosed with cancer and, thus, cancer treatments are becoming more complex and more costly [1]. Healthcare providers should meet not only cancer patients’ physical needs, but also their informational, psychological, social, and financial needs. Accordingly, some useful tools to deal with such purpose were provided, and concluded that by taking action and creating a partnership with cancer patients to consider all of their needs, whereas the likelihood of positive outcomes in all areas should be maximized [1]. Some factors were investigated, which can strengthen or impair flexibility or resilience and post-traumatic growth (PTG) in cancer patients and survivors [2]. Also, the relationship between resilience, PTG, and mental health outcomes was explored, and the impacts and clinical implications of resilience and PTG on the recovery process of cancer patients were discussed [2].

Cancer patients, undergoing active cancer treatments, were more concerned about the short-term effects of the Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the potential efficacy of ongoing cancer treatments and long-term effects, and systemic societal concerns that the general population is not concerned much about [3]. For example, the challenges faced by cancer patients in India during the COVID-19 pandemic were examined [4]. As a result, it was found that the majority (91.7%) of the cancer patients reported an increase in their anxiety levels due to COVID-19. However, cancer patients’ responses can be summarized as follows: deferral of radiotherapy appointments, long waiting hours after appointments, transportation problems from accommodations to hospitals, limitations of visitors and/or attendees, surgery postponements, deferral of oncology (tumor)-boards, dietician consultations’ delays, lack of peergroup support services and psychological counseling sessions, difficulty in maintaining precautionary measures, problems in availability and obtaining chemotherapy drugs, and so forth [4].

A study was conducted, in which an assessment was presented, regarding the needs of cancer patients, including provision of more effective support that is relevant to each patient’s specific needs, prioritizing the allocation of resources to serve cancer patients in a best way possible, and planning to provide comprehensive care designed to improve the cancer patients’ quality of life [5]. Also, the issue of “fear of progression (FoP)” or fear of improvement regarding cancer patients was investigated [6]. Accordingly, it was found that FoP is a major burden for adult cancer survivors, because FoP is significantly associated with depression, medical coping style, and decreased family functions.

Examples on difficulties, problems, limitations, and challenge facing cancer patients in the Occupied Palestinian Territories

The Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPT) is the focus of this research paper. The OPT is part of Historic Palestine which is part of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Arab region. The OPT has an area of about 6000 km2 that includes the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) and the Gaza Strip on the Mediterranean Sea. The OPT’s total population, as of January 13, 2023, was around 5.4 million [7].

Regarding some of the problems and challenges facing the Palestinian cancer patients in the OPT as being a conflict zone, they face significant barriers in accessing chemotherapy and radiotherapy, as well as palliative care and psychosocial support [8]. This is in addition to the COVID-19 impacts and consequences that the cancer patients have been facing, based on the fact that COVID-19 is considered, potentially, an additional risk of infection, which also results in indirect impacts on movement’s limitations and access to healthcare for cancer patients.

Some technical and healthcare challenges facing the oncology sector in the OPT have been addressed [9], which include: 1) Lack of specialized oncology services: Cancer care in the OPT has been fragmented without cooperation amongst oncologists, pathologists, surgeons, and radiologists. Medical care in the OPT is focused on cancer treatment with little emphasis on other elements of the cancer care continuum, such as prevention, early detection, screening, diagnosis, and follow-up during and after treatments, or during home-based follow-up. Also, comprehensive cancer care centers do not exist, except at the Augusta Victoria Hospital (AVH) in occupied East Jerusalem (discussed below in further detail). Cancer care is provided in isolated departments of governmental hospitals, where a few support services are available, such as palliative care, nutritional and psychological support, or rehabilitation services. These departments are often suffering from insufficient resources, including necessary equipment and medications, and trained human resources, particularly oncologists and oncology nurses. Due to the lack of specialized services, some cancer patients from the West Bank and Gaza Strip are referred to neighboring countries (such as Israel, Jordan, and Egypt) or to AVH in East Jerusalem; 2) Shortages of cancer specialists: The OPT is suffering from shortages of cancer specialists, including oncologists and others. In the OPT, there are only 5 radiation oncologists, 6 pediatric hematologists, 20 medical oncologists, 6 pediatric hematologists, 7 surgical oncologists, and 15 surgical pathologists, as being registered in the Palestinian Department of Health and the Palestinian Medical Council [9]. Thus, only one radiation oncologist and two medical oncologists are available per 100,000 population in the OPT, which is half the number seen in the USA and EU [9]; and 3) Cancer care’s capacity building: Considering the medical services offered to cancer patients at AVH in East Jerusalem, healthcare offered to cancer patients in the West Bank and Gaza Strip suffers, in general, from shortages including, amongst many others, trained staff. Accordingly, this sector is in urgent need for more trained and capacity-built professionals, including oncologists, radiologists, chemotherapists, physiotherapists, hematologists, psychologists, specialized oncology nurses, lab technicians, nutritionists, etc., in order to deal, professionally, with cancer patients and offer them good services to help them reduce their pain and stress.

Based on specialists in the fields of oncology, the cancer care system in the OPT badly needs oncology nurses as this is a specialized area and currently almost all nurses provide care in chemotherapy and radiotherapy, while inpatient oncology departments have general nurses who are not qualified in the field of oncology. In addition, three years ago, a Master’s program in “Oncology Nursing” began at Birzeit University, Birzeit, Ramallah, Occupied West Bank, and only ten nurses in oncology (representing only one group of students) graduated with a Master’s degree. Then the program was discontinued because it did not attract more nurses to specialize in this field. Nurses should be encouraged and offered an incentive plan to join such a specialized program, so that they can help provide better care for cancer patients in the OPT.

Briefing on cancer status in the OPT

In a study that has been recently published, it is indicated that the most common cause of death amongst all types of cancer in the OPT is the lung cancer in males (22.8%) and breast cancer in females (21.5%), followed by colorectal cancer in both sexes (11.4%) and prostate cancer in males (9.5%), as well as blood cancer (leukemia) in children (4.6%) [10]. Despite the small area of the occupied West Bank (5640 km²) and that of the occupied and besieged Gaza Strip (365 km2); together around 6000 km2 as mentioned above, regional or geographic differences were noted in possible cancer-specific causes of death, as well as in incidence and mortality rates, with respect to various kinds of cancer.

The central West Bank governorates recorded the lowest mortality rate for most types of cancer amongst males and females. The lung cancer’s mortality rate was higher in the northern parts of the West Bank amongst males. For prostate cancer, the mortality rate was higher in the northern and southern parts of the West Bank, and breast cancer mortality rate was higher in the southern part of the West Bank. Similar mortality rate patterns were also found in urban and rural areas and refugee camps in the occupied West Bank, as well in the Gaza Strip. The results in the West Bank’s governorates have shown different mortality rates of cancer, which can be explained by personal, contextual, and environmental factors that need indepth investigations. Further details about this distribution and other related topics can be found in [10].

4,779 new cancer cases and 2,895 cancer-related deaths were reported in 2020 [10-13]. As mentioned above, the most frequently reported types of cancer in 2020 were breast (highest in women), lung (highest in men), colorectal (highest in both sexes), and leukemia (highest in children). These are in addition to other types of cancer found amongst Palestinians in the occupied West Bank and occupied and besieged Gaza Strip (Table 1).

Table 1: Cancer types in both sexes, as well as in males and females separately, amongst Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza Strip for the year 2020 (after [10,11]).

| Both sexes | Males | Females | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Cancer Type | No.of Cases | Percentage | Rank | Cancer Type | No.of Cases | Percentage | Rank | Cancer Type | No.of Cases | Percentage |

| 1 | Breast | 892 | 18.7% | 1 | Lung | 436 | 19.2% | 1 | Breast | 892 | 35.6% |

| 2 | Lung | 547 | 11.4% | 2 | Colorectal | 274 | 12.0% | 2 | Colorectal | 246 | 9.8% |

| 3 | Colorectal | 520 | 10.9% | 3 | Prostate | 191 | 8.4% | 3 | Thyroid | 150 | 6.0% |

| 4 | Leukemia | 219 | 4.6% | 4 | Bladder | 145 | 6.4% | 4 | Lung | 111 | 4.4% |

| 5 | Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (NHL) | 216 | 4.5% | 5 | Lukemia | 124 | 5.5% | 5 | Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (NHL) | 104 | 4.2% |

| 6 | Other Types | 2,835 | 49.9% | 6 | Other Types | 1,104 | 48.5% | 6 | Other Types | 1,002 | 40% |

| Total | 4,779 | 100% | Total | 2,274 | 100% | Total | 2,505 | 100% | |||

The situation in the Gaza Strip is much worse and more complicated than that in the occupied West Bank. This is due to the fact that the Gaza Strip, with a population of approximately 2.2 million and a tiny area of only 365 km2(as indicated above) was attacked, during the last 10-12 years, by Israel in 5 wars. In addition to the several confrontations and Israeli intrusions within the Gaza Strip, these are the all-out wars (or heavy military operations) launched by Israel on the Gaza Strip: i) 27 December 2008 – 18 January 2009; ii) 8 June 2014 – 26 August 2014; iii) 10 May 2021 – 22 May 2021; and v) 5 August 2022 – 7 August 2022 [14,15].

Work’s purpose

This research paper presents original research that documents an important health issue from the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPT: the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip). This paper is remarkable, because it is the first of its kind, as it, critically, objectively, and bravely, investigates substantial issues affecting the cancer patients in the OPT, as significant issues have been appropriately investigated, argued, and well documented and presented. This paper focuses on cancer patients in the OPT, as a conflict zone, linking conflict and health, with particular emphasis on the difficulties, problems, limitations, challenges, and corruption facing Palestinian cancer patients in the OPT, as being greatly a complicated region, socially, economically, politically, humanely, and is poorly served, health-wise.

This work is primarily a continuation of the work carried out by the same author, regarding the cancer status in the OPT, which has been published just recently in a Springer’s leading specialized journal on oncology [10]. The already published work [10] deals with the science of cancer in the OPT, cancer’s various types, its rates of incidence and mortality, its potential causes, and other related issues. Meanwhile, this current work investigates social perspectives related to cancer patients’ health, mentally and physically. The paper presents original research that is not published previously, focusing on cancer survivors, analytical reviews, clinical investigations, sociology, politics, geopolitics, and policy research. The paper also focuses on improving the understanding and management of the multiple areas that can affect quality of care and quality of life of cancer survivors, symptom’s management, functioning, and well-being.

Data and methodology

For the previous research paper [10], data on cancer incidence and mortality rates for the OPT were collected, analyzed, and interpreted. In the current paper, the research is primarily based on desk reviews of the available documents and literature, plus a few interviews conducted with some people concerned. The literature review, for which the Google search engine was used, was based on publications that are available on the Internet in the form of scientific papers or technical reports prepared by international organizations. However, the published works related to the issues investigated in the OPT, in particular, are very few. Some issues discussed in the current paper are available on the Internet via a YouTube which was also used in the analyses of the data obtained.

The interviewees, who requested anonymity regarding their number and identities, included cancer patients, some of their family members and friends, general practitioners, and others involved. Interviews, conducted at random, were made privately via phone, social media, and in-person at other times. As required by the interviewees, strict consideration was given to confidentiality and privacy in the analysis, discussion, and presentation of the data obtained. On the other hand, some patients and their relatives and friends, as well as general practitioners and others involved, denied interviews due to the sensitivity of the subjects examined. Due to the fact that confidentiality and privacy have been fully observed, respected, and guaranteed when data obtained, no identities, numbers, and any other related personal information are provided in the present paper and, thus, there is no need for consent. Therefore, the data obtained, analyzed, discussed, and presented in this paper are general, with the aim of making the public aware of the issues investigated, researched, and presented in this paper, with the focus on the difficulties, problems, limitations, and challenges – DPLC – facing Palestinian cancer patients in the OPT. Other data were collected, interpreted, and discussed in relation to corrupt behaviors in relation to the issues examined in this paper (DPLC), in particular, and the cancer situation in the OPT, in general.

With regard to the statistical analysis of the data obtained and presented in the paper, and because of the sensitivity of the subjects investigated, statistics and uncertainty in the data are not applied; simply because the data provided are taken directly from authentic sources that include patients with cancer and others within the same circle. However, the data and findings are presented in a logical manner that makes sense in light of the objectives involved, the questions posed, and the problems investigated. Therefore, care has been taken to present, organize, and discuss the topics of this paper rather than relying on the outputs of statistical analysis.

Results and discussion

Cancer Patients’ treatment and recent denial of treatment at the Augusta Victoria Hospital (AVH) (Almuttal’a Hospital) in Occupied East Jerusalem

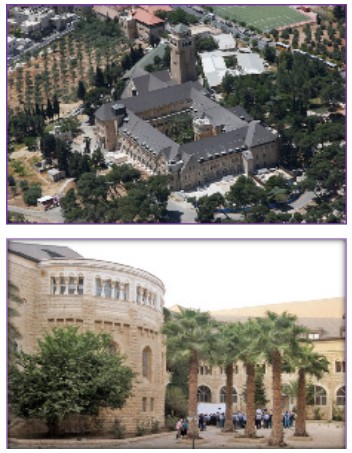

Regarding treatment of cancer patients in the OPT, the situation can simply be described as “miserable”. Cancer patients in the occupied West Bank and the occupied and besieged Gaza Strip go to the Augusta Victoria Hospital (AVH; also known as “Mustashfa Al-Muttal’a”, in Arabic) in East Jerusalem (Figure 1), though their number has been considerably decreased due to the factors mentioned below.

The complex (Figure 1) was built in 1907–1914 by the Empress Augusta Victoria Foundation, as the center of the German Protestant community in Ottoman Palestine and the Church of the Redeemer in the old city of Jerusalem [16]. In addition to the hospital, the complex also includes the German Protestant Church, a meeting center for pilgrims and tourists, an interfaith kindergarten and a cafe, as well as the Jerusalem branch of the German Protestant Institute of Archeology. During most of its history, the complex was used first and foremost as a hospital, either by the military (during the First and Second World Wars and during the Jordanian rule on the old city of Jerusalem), or for Palestinian refugees and the general public (from 1950 until present), and as governmental or military headquarters during 1915—1927 [16].

The Augustus Victoria complex is a church-hospital complex located on the north side of the Mount of Olives in East Jerusalem, and is one of six hospitals in the East Jerusalem Hospital Network (EJHN). The network (EJHN) plays an important role in the Palestinian healthcare system. EJHN includes Al-Makassed Hospital, Augusta Victoria Hospital, Red Crescent Maternity Hospital (also called Palestinian Red Crescent Society Hospital), St. John’s Eye Hospital, Princess Basma Rehabilitation Center, and St. Joseph’s Hospital.

The first largest one is Al-Makassed Hospital “Mustashfa Al-Makassed” (in Arabic), which is a Palestinian Arab hospital that belongs to the Makassed Islamic Charitable Society. The Augusta Victoria Hospital is the second largest hospital (after Al-Makassed Hospital) in East Jerusalem. It is a non-profit, nongovernmental organization run by the Lutheran World Federation [17]. It is the only remaining specialized care unit located in the OPT (West Bank and Gaza Strip), and is considered the leading cancer treatment’s center in East Jerusalem and the rest of the Occupied Palestinian Territories. Today, AVH provides specialized care to Palestinians from all over the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, with services including a cancer center, dialysis unit, and pediatric center, and in 2016, AVH inaugurated a bone marrow transplantation unit [18]. The medical treatments offered by AVH to cancer patients include chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and nuclear medicine scanning, as well as certain specialist surgeries [12,13,19].

Unfortunately, since September 2021 AVH has refused to take new cancer patients from the West Bank and the Gaza Strip for cancer treatment, and as of the end of March 2022, nearly 500 cancer patients have been denied treatment in the hospital [12,13]. “Patients with cancer have been turned away from the key Palestinian cancer center because the hospital [AVH] cannot afford the costly chemotherapeutic drugs and other cancer treatments, owing to the non-payment of an outstanding USD 72 million from the Palestinian Authority [PA], which is expected to provide funds for Palestinian patients’ cancer treatment” [12, 13]. This is with the consideration that cancer treatments in the Occupied Palestinian Territories (the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip) are considered as a national initiative, as PA covers the costs of treatments in both public and private cancer centers for all Palestinian cancer patients.

However, based on personal experience of some specialists in the field, it is claimed that the costs of cancer care and treatment are covered at 100% by PA; however, this is not the case. Since the Palestinian Ministry of Health puts many conditions in its agreements with private hospitals, such as AVH, to provide only certain treatments, such as chemotherapy or radiotherapy, and this coverage includes (sometimes) and excludes (other times) the very minimum of certain drugs that a cancer patient may need to deal with the side effects of chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or any other treatments, emergency care, or admission’s events required as a result of the treatment. Cancer patients receive doses of chemotherapy and are sent home where they have to suffer alone from the side effects of treatments. And if they are lucky they probably know someone who can prescribe them a drug to buy it and pay for it on their own, which may help them cope with pain or not. Another group of cancer patients is that who can use and apply some tips and tricks to manage their cancer treatment. Some other groups of patients who may have good connections with officials having power and can use it efficiently and effectively.

The additional types of supportive therapies are urgently needed for cancer patients to cope with the overwhelming treatment modalities used in treating cancer, which pose a huge additional financial burden on cancer patients during treatment. Coverage of these additional therapies may vary between patients, depending on their political affiliations or positions in the Palestinian Authority. The coverage packages and inclusions/exclusions, which may be different amongst cancer patients, are clearly stated on the referral form, representing an example of unequal access to cancer treatment and injustice in obtaining it. As East Jerusalem’s hospitals – EJHN – face financial difficulties and suffer dire consequences, the good news is that the US President – Joe Biden – during his latest visit to the Holy Land in July 2022, announced a USD 100 million multi-year commitment to EJHN, of which AVH is a member, as mentioned above. President Biden also welcomed the United Arab Emirates’ USD 25 million contribution, and encouraged other countries in the region and the world to increase their contributions to support “the vital work that is being done here,” who continued, “I am honored to be able to see the service and quality of care you provide to the Palestinian people. These hospitals are the backbone of the Palestinian healthcare system” [17]. The other good news is that the European Commission approved, on 14 June 2022, a new bilateral allocation to the Occupied Palestinian Territories, worth Euro 224.8 million [20]. This new assistance package will support the Palestinian Authority and vital projects in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. This package complements previous contributions, such as Euro 92 million in support of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA), bringing the total EU’s assistance to the Palestinians in 2021 to Euros 317 million, which does not include another Euro 25 million in humanitarian funding announced in May 2022. The European Union (EU) expects to provide the Palestinian Authority up to Euro 1.152 billion in financial support from 2021 to 2024 [20]. International entities, such as the European Union, and international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) are keen in helping the Palestinian people under occupation.

As recently (3 August 2022), the usual influx of cancer patients from the West Bank and Gaza Strip has significantly decreased due to a lack of funding that pushed AVH to refuse patients or reduce their number since September 2021, as mentioned above. The AVH’s Deputy CEO – Fadi al-Atrash – said, “It’s the first time in our history that we’ve been forced to take the decision not to accept new patients. We might have to stop the treatment of patients already in our care, [meaning] that more people might die of cancer because they’re not receiving their treatment on time, or according to the right schedule” [21]. “Augusta Victoria Hospital (AVH) in East Jerusalem has been turning away terminally ill cancer patients due to the lack of sufficient international funding received for treatment. The Hippocratic Oath is put ‘on hold’ as politics is given precedence over Palestinian healthcare” [21].

Cancer patients’ treatments in the occupied West Bank

In the occupied West Bank, cancer patients used to go for treatment to AVH in East Jerusalem until September 2021, which is due to the Palestinian Authority’s unpaid due-bills to AVH, as discussed above, though AVH currently takes a much smaller number of the West Bank’s cancer patients. A new cancer-care facility, known as Oncology-Hematology Center (OHC), has been opened at Beit Jala Governmental Hospital (BJGH, also known as King Hussein Hospital – a publically administered hospital) in Beit Jala, Bethlehem governorate, occupied West Bank. The BJGH’s OHC was established as a project funded by the Italian government as part of Italy’s campaign to improve the quality of healthcare for Palestinians in the OPT, and was implemented by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) [22]. OHC provides screening, diagnosis, and treatment of tumors and related blood disorders. It offers comprehensive services for adults and children, including daycare, outpatient clinic, histopathology laboratory, and diagnostic endoscopy unit for examining internal organs. Furthermore, the American Near East Refugee Aid (ANERA) rehabilitated BJGH, including the lab, the endoscopy and X-ray departments, male and female surgery wards, the emergency and operations units, medical staff residents, hospital roof and the pharmacy. In the village of Harmala (discussed below in further detail), ANERA has rehabilitated and expanded the Harmala clinic [23].

As a governmental hospital in the OPT, BJGH provides more treatment than before for Palestinian cancer patients, considering the fact that cancer patients have been recently denied treatment at AVH in East Jerusalem, as already mentioned. However, at present, although not on a large scale, there are a few other units in government hospitals that offer cancer treatment to Palestinian cancer patients. There is a new oncology unit at the Palestine Medical Complex (PMC) in Ramallah (central area of the West Bank), offering different types of chemotherapy and follow-up treatment, which is run by a few, well-trained oncologists assisted by a few nurses and lay doctors. However, this unit at PMC is relatively small compared to the number of cancer patients who visit it daily for treatment and follow-up, and also compared to other large units with sufficient space, offering various kinds of medical services in the same complex – PMC – which are well-serviced but receive much fewer patients. Again, this is an example of the lack of priority given to cancer care in the OPT, the inequity of space allocation, and the distribution of medical care available in Palestinian hospitals, representing another bad example of power and politics. A new, but small, oncology unit has also been launched at Rafidia Hospital, which is a governmental hospital in the city of Nablus (northern West Bank), providing diagnosis and treatment for breast-cancer patients. According to a specialist in the field, the medical team, however, is still undergoing training and capacity-building activities by external visiting oncologists and oncology nurses from the United Kingdom via funding agencies. There was also a plan to start a cancer care unit in Al-Khalil Governmental Hospital (Alia Hospital) in the city of Hebron (southern West Bank) to start operating on a small scale [24]. However, the unit was cancelled by the Ministry of Health for unknown reasons. Cancer patients in the city and government of Hebron, southern the West Bank, are currently calling for the establishment of a cancer treatment’s unit in Hebron to save them the trouble of travel and the suffering that they have to face when they go to the “Palestine Hospital (PH)”, also known as “Harmala Hospital” in Bethlehem, as discussed below in further detail [25].

Based on what is said and witnessed by some cancer patients and their relatives, many of the patients still prefer, if allowed, to go to AVH in East Jerusalem because of the treatment’s high quality evidence-based services that the hospital offers to them, in comparison with services offered at other hospitals in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. However, BJGH in Beit Jala provides services and accommodates most cancer diseases in the West Bank, in addition to the presence of the only pediatric leukemia department, which was established in 2013.

In April 2013, the Palestine’s Children’s Relief Fund (PCRF) opened the first public pediatric cancer center in BJGH, which has received donations from generous donors around the world. The department was named “Huda Al-Masri Children’s Cancer Department” after the founding social worker, Hoda Al-Masri, who died in 2009 of leukemia [26]. Since its opening, hundreds of sick children have received specialized medical care, regarding cancer treatment. In February 2019, PCRF opened the Pediatric Cancer Department, with the name of “Dr. Musa and Suhaila Nasser” in Gaza city, as being the first pediatric cancer center in the Gaza Strip. Both pediatric cancer centers (in Beit Jala in the occupied West Bank, and in Gaza city in the occupied and besieged Gaza Strip, which are privately funded) provide Palestinian children from all over the West Bank and Gaza Strip with cancer care for free.

Transferring cancer patients for treatment to the Palestine Hospital (PH) In Harmala, Bethlehem Governorate

In January 2022, the “Palestine Hospital” – PH – for military medical services was opened in the town of Harmala, Bethlehem government, occupied West Bank, in order to serve the patients of COVID-19. PH was later considered as part of BJGH to treat cancer patients who come to the hospital from various regions of the occupied West Bank to receive cancer treatment, particularly, chemotherapy.

The Palestinian cancer patients face several problems during their visits to PH in Harmala. These problems may include: 1) The hospital – HP – is located in a remote area (Haramla), where there is no means of transportation to take cancer patients to the hospital and bring them back to their gathering’s location; 2) This puts cancer patients under heavy burdens of additional physical effort and additional financial expenses, since they have to take taxis with higher costs, plus the additional time they have to spend on transportation, waiting, and treatment; 3) There are no good services, laboratories, kitchen, and sufficient medical and nursing staff; 4) The lack of special dining tables to serve cancer patients, so that they can take meals while sitting in their beds and while being treated for cancer; 5) Meals come from BJGH in an unhygienic manner, where food is put in cork boxes, plus unrefrigerated and unsealed containers of yoghurt; and 6) In most cases, medications are not available and, therefore, cancer patients must buy them from pharmacies at their own expense; this is if they can offer the price, because, most likely, the medications are very expensive.

Based on recently published YouTube video [25] and report [27] (both in Arabic), Palestinian cancer patients and their relatives are complaining about the poor services provided to them at the Palestine Hospital in Harmala, Bethlehem. Some people reported that transferring cancer patients from the OHC of BJGH in Beit Jala to PH in Harmala represents negligence and marginalization of cancer patients and a great failure in serving them properly, humanely, and professionally. A woman with cancer said, “When they decided to send us to Harmala [Hospital], they sentenced us [cancer patients] to death. I went twice [to Harmala Hospital] and I will never go back. There is no service, no treatment, and no imaging [medical screening], and even transportation [to Harmala Hospital] is torture. Also, they did not give me a report, stating that I had a medical examination there” [25].

Another problem facing cancer patients is that they are randomly transferred to different hospitals in the occupied West Bank. Accordingly, cancer patients are sometimes transferred to Palestine Hospital in Harmala – Bethlehem, sometimes to AVH in East Jerusalem, and other times to the Istishari [Consultative] Arab Hospital in Ramallah. These transfers are based on poorly understood criteria, and without following an approved protocol for cancer patients’ treatment. Sometimes transfers are made because chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and/or any other needed and related treatments are not available in this or that hospital or at the Palestinian Ministry of Health. This behavior (transferring cancer patients from one hospital to another) leads, definitely, to negative impacts on cancer patients. The negative impacts of such practices on cancer care include, for example, that frequent changes of the location of treatment for cancer patients disrupt their treatment protocols, which may result in negative impacts on the effectiveness of the treatment they receive and, thus, affect their prognosis, improvements, well-being, and survival.

Considering the above, most cancer patients do not know: i) what is the next stage of treatment; ii) to which hospital they should go for the next visit or referral after 15 days; iii) what kind of examinations and/or treatments needed for them during their next visit/referral to this or that hospital; and iv) are those examinations chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and/or any other treatments that may be required for cancer patients? This can be really difficult on cancer patients and their family members. It is also difficult to deal with when cancer patients should wait for something unknown; such as when and where to go and for what reason. Accordingly, waiting for such unknown matters can be a scary time for cancer patients and their beloved ones, so that they possibly experience some strong emotions, including disbelief, anxiety, fear, anger, and sadness, which may lead to chronic depression. Such reactions can, certainly, lead to further deterioration of cancer patients and uncomfortable feeling of their family members.

Cancer patients’ treatment in the occupied and besieged Gaza Strip

Because of the prolonged shortages of cancer drugs in the public health system in the occupied and besieged Gaza Strip, most cancer patients, requiring chemotherapy and other types of cancer treatment, used to be referred to hospitals outside the Gaza Strip, particularly AVH in East Jerusalem until September 2021, as indicated above. Some other types of cancer treatments, including advanced diagnostic services, palliative care, radiotherapy, nuclear medicine, and specialized surgeries, are not available in the Gaza Strip’s hospitals. Moreover, by the end of April 2020, the stock of 54% of oncology drugs in the Gaza Central Drug Store was less than a month’s stock, meaning that no more drugs were available for cancer patients in the Gaza Strip.

What adds insult to the injury is the fact that cancer patients in the Gaza Strip, as well as in the West Bank, must go through a great deal of extra suffering. The extra suffering is exacerbated by the uncertainty about the process required to obtain an exit permit issued by the Israeli occupation authorities, in order to allow them visiting AVH in East Jerusalem for cancer treatment. This is in addition to the difficulties that cancer patients encountering during their travel to AVH in East Jerusalem. This is crystal clear as cancer patients must go through exceptional security checks at Israeli occupation’s military checkpoints. However, the approval of obtaining an Israeli permit is not guaranteed, as no less than 35% of applications are rejected by the Israeli occupation authorities [19]. Typically, most unapproved applications usually do not receive any responses (neither positive nor negative) from the Israelis occupation authorities by the time their AVH’s appointments are due. This, in turn, enforces cancer patients to reschedule their AVH’s appointments and submit new permit’s applications, which means another cycle of waiting that may take several days or even weeks, in order to receive approval from the Israeli occupation authorities to enter occupied East Jerusalem for treatment at the Augusta Victoria Hospital.

The outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic in 2020 and its continuation in 2021 and early 2022 had caused increased stress and difficulties for cancer patients, and created additional obstacles for them [28]. These include, for instance, travel limitations, vaccinations, extra travel permits, using masks all the time, extra financial costs, and so forth. The new arrangements, due to COVID-19 epidemic, have added additional problems and difficulties to the already existing ones that cancer patients usually face when they go to AVH for cancer treatment in occupied East Jerusalem, especially at the hands of the Israeli occupation authorities. Such limitations and difficulties, accordingly, have enforced cancer patients (or some of them) to find alternatives for having chemotherapy treatment instead of going to AVH in East Jerusalem. Therefore, in the Gaza Strip cancer’s patients go to Al Haya Specialized Hospital in the Gaza city, which is a privately owned and administered hospital.

In light of these briefly described difficulties, problems, limitations, and challenges – DPLC – that face cancer patients in the Gaza Strip, making some chemotherapy services available on a large scale in the Gaza Strip will relatively alleviate some of the DPLC encountered by cancer patients. This will also spare cancer patients the difficulties and uncertainties of the complex system of the Israeli permit that they must obtain before each of their visits to AVH in occupied East Jerusalem, the burdens of traveling long distances and crossing many Israeli military checkpoints, the family separation, and the need to remain in quarantine upon return, in addition to the extra financial expenses. However, putting a lot of difficulties and creating many more problems for Palestinian cancer patients by the Israeli occupation authorities has intended to reduce the number of Palestinians from going to AVH and completely preventing them from entering the old city of Jerusalem. Here medicine, health, pain, suffering, humans, and humanitarian issues are typically mixed with unbalanced, unjust, inhumane, and unfair policies and immoral politics that terribly affect cancer patients, while many of them are perhaps living their last days, weeks, months, or some years.

There are still significant gaps in the services provided to cancer patients in the Gaza Strip as well as in the West Bank, including chemotherapy and other types of treatment, while basic facilities for adequate screening and cancer treatment are still unavailable. However, the recent availability of some chemotherapy in Gaza (and, to that matter, in Beit Jala, West Bank, as discussed above) has brought a lot of relief to people in extremely vulnerable situations and, therefore, all efforts must be made to maintain these achievements, though they are small. In addition, the limitations imposed by the Israeli occupation authorities must be completely and immediately ended, based on the obligation to treat cancer patients fully with respect, dignity, and humanity, by allowing them to travel smoothly and let them pass easily through the Israeli military checkpoints in the areas controlled by the Israeli occupation authorities, especially when they need to go to AVH in occupied East Jerusalem for cancer treatment; such measures must be taken by the Israeli side. On the other hand, the Palestinian Authority must repay its debts to AVH and other hospitals in occupied East Jerusalem and the rest of the West Bank, so that cancer patients from the Gaza Strip and West Bank can be able to comfortably have treatments at AVH and/or other hospitals, without fear that they will be sent back to their homes without treatment, because of the PA’s debts, based on previous experiences.

Cancer-related corruption files and their impacts on cancer patients and the state of cancer in the OPT

Corruption of the Palestinian Authority (PA): Corruption is a widespread phenomenon within the Palestinian Authority’s ministries and institutions, the private sector, and Palestinian NGOs. Therefore, corruption in the Palestinian Authority and society is described by some observers as “a cancer that eats the flesh of the Palestinian people under occupation,” whose effects are no less painful and negatively impactful than the Israeli occupation, as it (corruption) has extended to all segments of Palestinian society [29-35]. “Palestinians recently ranked corruption as the second largest problem after the economic crisis – higher than the Israeli occupation. Palestinians generally view Palestinian Authority (PA) officials as a self-serving, elitist group disconnected from the Palestinian struggle and the people’s daily suffering. Despite this dissatisfaction, there has been little change. What remains are the “old guards” maintaining a grip on power, rampant and systemic corruption, and the alienation of Palestinians from participation in decisions that impact their lives and future” [30].

Unfortunately, corruption has reached advanced levels and, thus, become a very painful and negatively impactful issue, particularly with respect to cancer patients in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. This is due to the fact that corruption has negatively affected the state of cancer and the conditions of cancer patients in the OPT. It is worth noting that international entities, such as the European Union and others, are very keen on their taxpayers’ money that EU provides to the Palestinian Authority to help Palestinians who have been living under the Israeli military occupation since June 1967 and continuing, and those who have been living as refugees in miserable refugee camps since 1948 and continuing (i.e., since the creation of the state of Israel in Historic Palestine in May 1948). A report prepared by the EU stated that financial corruption in the Palestinian Authority led to a “loss” of aid amounting to about 2 billion Euros, which were transferred to the Palestinian Authority to serve Palestinians in the occupied West Bank and occupied and besieged Gaza Strip during the period 2008–2012 [29].

However, there is a significant imbalance in the spending and management of international aid that comes to the Palestinian Authority. Here politics is heavily mixed with health-care, socioeconomics, and other societal issues. “For Palestinians, the problem is deeply rooted in more than just the policy inclinations of their leaders. That leadership itself has decayed and lost much of its ability to shape Palestinian political horizons and strategic thinking. Palestinian leaders and institution do little policymaking, pursue no coherent ideology, express no compelling moral vision, are subject to no oversight, and inspire no collective enthusiasm. The problem goes beyond the corruption that has been an issue in the past to a pattern of disengagement from any practical state-building efforts” [36]. Accordingly, the European Union and other international entities and organizations need to pay more attention, regarding the financial aids offered to the Palestinian Authority. According to the United Nations: “Without good governance – without the rule of law – no amount of funding, no short-term economic miracle will set the developing world on the path to prosperity. Without good governance, the foundations of society – both national and international – are built on sand” [37].

According to RAND Corporation, which is an American nonprofit global policy think-tank created in 1948, conducting research to develop solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous [38]: “Good governance will be a key measure of success of a new Palestinian state. From our perspective, this must include governance that is representative of the will of the people, practices the rule of law, and is virtually free of corruption…... Finally, the authoritarian practices and corruption that has characterized rule under the Palestinian Authority must be eliminated….. According to evidence presented at a recent World Bank conference16 the Palestinian Authority’s effectiveness, ability to control corruption, and institution of a viable rule of law have plummeted over the past several years….. The corruption is grounded in the personalized nature of power and appointments” [39].

According to the report published by the Middle East Monitor (MEM): “The report was written after EU monitors visited Jerusalem, Gaza and the West Bank and told of their inability to confront “high-level risks” such as “bribes and misuse of aid”. The newspaper also reported that the EU may take measures to reduce the budget allotted to the Palestinians or, at least, monitor more closely the money being transferred. This is not the first report regarding the corruption of the Palestinian Authority, as it has been accused of corruption since its establishment. Many examples have come to light of Palestinian officials accused of corruption” [29].

As related to the Palestinian Authority’s health sector, in particular, “The ghost hospitals are grotesque symbols of the cronyism and wastage that dogs the PA [Palestinian Authority’s] health sector, which has soaked up more than £200 million of British taxpayers’ cash since 2008…. Palestinian patients seeking treatment in Israel, who do not have powerful political friends, must pay bribes to corrupt PA officials to get referred…. The debt-ridden PA wastes millions by sending patients to expensive private hospitals when its public facilities could provide the same treatments at a fraction of the cost” [40].

The case of cancer patient – Saleem Nawati (16-year old boy): Regarding the link amongst corruption, cancer patients, and other related issues, the death of the 16-year-old leukemia patient – Saleem Nawati – has revived accusations of “nepotism” and mismanagement against the Palestinian Authority [41]. Saleem Nawati, a resident of the occupied and besieged Gaza Strip, was prevented from entering An-Najah National University Hospital (NNUH) in the city of Nablus, northern West Bank. He was diagnosed with leukemia (blood cancer) in November 1921, but like all other cancer patients in the occupied and besieged Gaza Strip, he had to wait weeks to obtain an Israeli medical permit, in order to be allowed to travel to the West Bank for treatment. S. Nawati arrived with his uncle – Jamal Nawati – to the West Bank city of Ramallah on December 26, 2021 after they obtained the Israeli permit. After all of that and associated suffering, NNUH refused to admit him for treatment, citing a dispute with the Palestinian Authority’s government over unpaid hospital bills; a similar situation to that between PA and AVH, as previously discussed. On January 9, 2022, the PA’s Ministry of Health in Ramallah announced the death of Saleem Nawati, whose death was announced shortly after an ambulance removed his body from the Ministry’s office [41].

Another example of official corruption, taking place in the institutions of the Palestinian Authority, is the “Khaled Al-Hassan Hospital for Cancer and Bone Marrow Transplant Project” (KAHHP) – a notoriously infamous project that never saw the light of day, although its foundations were laid in 2016. Below is more detail about this failed project (KAHHP), representing a very shameful scandal for the Palestinian Authority.

Khaled Al-Hassan Hospital for Cancer and Bone Marrow Transplant Project (KAHHP): The Palestinian Economic Council for Development and Reconstruction (PECDAR) assumed the responsibility’s leadership, regarding the construction of KAHHP. The project was designed to be built on the land of Surda town near the city of Ramallah in the occupied West Bank at a cost of USD 140 million (Figure 2–Upper), which does not include the costs of medical facilities and equipment, according to PECDAR [42].

However, it was believed that the establishment of a hospital of this size would constitute a qualitative leap regarding the Palestinian medical services provided to cancer patients in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, and that would save nearly 80% of the treatment bill allocated to cancer patients abroad. It was also believed that the hospital, more importantly, would end the suffering of Palestinian cancer patients and their families, when they navigate through Israeli barriers and military checkpoints, facing humiliation and suffering, as well as complicated procedures in order to obtain Israeli medical referrals, as discussed above.

In June 2016, the Palestinian Authority’s President – Mahmoud Abbas – laid the foundation stone for KAHHP, announcing the start of work to establish the largest medical edifice in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, as being the first of its kind in the region and one of the rare projects in the world [40,42] (Figure 2–Upper). President Abbas had assigned PECDAR to implement and supervise the project (KAHHP). From that moment on, PECDAR formed an engineering team that worked alongside a medical team to manage the files of the project and put the plans for its establishment. In March 2017, “Brothers Contracting Company” won the excavation’s bid with a contract valued at USD 2.924 million [42]. At the end of February 2018, PECDAR launched the first site of the project’s construction, which was the excavation stage (Figure 2–Lower), whereas PECDAR’s crews estimated the amount of excavated material at 394,000 m3 of rocks and soils. The excavation’s works were tendered to buy time, considering that the excavations were supposed to be for 4 basement’s floors that could go down to 20 m underground, and which would take about 8 months of work [42].

The construction area of the project was supposed to be about 100,000 m2 (equivalent to 100 dunams, which is the cadastral unit used in Palestine). This area was supposed to include the medical space and auxiliary facilities, such as auto parking, laundry, kitchen, cafeteria, etc. The net medical area was supposed to be around 52,000 m2 designed to accommodate about 208 beds. This includes the hospital’s building and its medical facilities (patients’ rooms, waiting’s rooms, operation’s rooms, equipment’s rooms, clinics, laboratories, emergency, palliative care, etc.). The building was supposed to consist of 15 floors, of which four underground floors including two floors for parking and some other facilities. The area of each of the floors was supposed to be around 12,000 m2.

The question is: What happened after that? As a matter of fact, there is no available concrete answer to this question except the pictures shown in Figure 2 (Upper and Lower). A whirlwind of questions was raised by the public after the death of the 16-year-old boy – S. Nawati – from Gaza, as previously discussed, while he was waiting for cancer treatment at the gates of hospitals in the occupied West Bank. The interest of angry citizens was intensely focused on the delay of the Palestinian Ministry of Health in Ramallah to grant the boy – S. Nawati – urgent approval to obtain a medical referral to NNUH in Nablus city or to any other hospital in the West Bank to keep him alive, as related to the hypothetical and failed “Khaled Al-Hassan Cancer Hospital and Bone Marrow Transplant Project”. This is of particular importance, especially due to the fact that 7 years have passed (2016–2023) and more years to count since the official call was announced to launch KAHHP – the project that has not yet seen the light until this minute. This simply means that millions of dollars have evaporated, which are probably no less than USD 10 million, although no one knows exactly how much money has been lost or wasted in this hypothetical, failed project (Figure 2–Upper and Lower). This leads to the other question: Where did those millions of dollars go? The easy and straightforward answer is: Nobody knows.

According to allegations of the Palestinian Authority’s Ministry of Health in Ramallah, the reason for not implementing the Project – KAHHP – was due to: “The lack of necessary funds and, therefore, it [the project] has been frozen at the present time, as the Ministry and the Government are working to provide financial support for the establishment of the project” [45]. It is noteworthy that no one knew about the scandalous corruption case related to KAHHP until the death of the boy from Gaza, who had leukemia, as he died immediately after he was denied treatment. This means that the boy’s tragedy led to reveal another national tragedy at governmental level in the Palestinian Authority.

Palestinian activists (political, social, legal, human rights, etc.) stressed the need to reveal the truth about KAHHP. They also stressed the need for clear answers about the presence or absence of suspicions of corruption, mismanagement, and failure to follow up on the project. Furthermore, such factual information about KAHHP must be based on real findings, accountability, transparency, and prosecution demands. Activists also stressed the need to form an independent investigation’s committee from all relevant parties, excluding, in particular, the Council of Ministers and the Ministry of Health, as well as PECDAR. Such a committee must listen to the testimonies of all concerned, involved, and interested individuals and parties, and should be granted access to all related and required information. Activists also stressed that it is necessary for the public to know the truth, and it is the responsibility of all relevant and concerned institutions to disclose to them all available data and details about the project – KAHHP. These data and details should be submitted to the Anti-Corruption Commission and the Office of Financial and Administrative Oversight, as well as the Independent Human Rights Commission and AMAN Transparency, in partnership with other civil society organizations, in order to form a unified fact-finding about KAHHP, and to provide trustworthy findings to the public.

As a result, many years have passed since the launch of the project – KAHHP – in June 2016, and several months have passed since the death, in January 2022, of the boy (Saleem Nawati, 14 years old from the Gaza Strip), who was sick with cancer and was left to die without being allowed to be treated. The Palestinian Authority is well aware that the Palestinian people are under heavy burdens of problems, politically, socially, economically, financially, educationally, healthily, etc. In view of this event and dozens of other similar events, the Palestinian public strongly believes that the Palestinian Authority always bets that people forget over time. This bet has been proven correct. KAHHP, as a humanitarian project that hoped to alleviate the suffering of cancer patients, was actually a “mock project” and proved to be a “high-profile scandal,” as many observers in the OPT describe it. Donations collected for this project amounted to USD 10 million and 12 million New Israeli Shekels (NIS – the currency used in the OPT), which together make up about USD 13.5 million [46].

More details about the Palestinian Authority’s corruption, regarding the death of the boy with cancer from Gaza – Saleem Nawati – and the mismanagement of the funds collected for the establishment of the Khalid Al-Hassan Cancer Hospital and Bone Marrow Transplant Project, can be found in many articles in Arabic, English, and other languages as well. These are some examples, amongst many other articles [40-52].

Conclusions and recommendations

Cancer is a disease associated with serious physical, emotional, social, and financial problems and consequences for affected individuals and their family members. Accordingly, healthcare professionals, as well as decision- and policy-makers, and politicians should facilitate easy and comfortable transition of cancer patients into the medical care system, in order to reduce their stress and maximize their clinical outcomes, as well as bring them, gradually, back on track, when/if possible.

Cancer, with its diversity, is the second group of diseases after cardiovascular diseases in the Occupied Palestinian Territories – OPT, which consists of the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip, with a total area of about 6,000 km2 and a total population of about 5.4 million. In 2020, there was 4,779 new cancer cases and 2,895 death cases, whereas the most frequently reported cancers included breast (in females), lung (in males), colorectal (in both males and females), and leukemia (in adolescents and children).

In addition to their suffering from cancer diseases, Palestinian cancer patients face many difficulties, problems, limitations, and challenges, as well as corruption events. These include the long wait for several weeks to obtain the Israeli permits to be allowed to go to occupied East Jerusalem for cancer treatment in high-quality and well-equipped Palestinian hospitals, as these hospitals are under complete control by the Israeli occupation authorities. In order to obtain such permits to visit specialized hospitals in occupied East Jerusalem, Palestinian cancer patients often miss their appointments for treatment in East Jerusalem’s hospitals, which means that they have to repeatedly apply for hospital appointments and Israeli permits to go to occupied East Jerusalem. This means that they have to keep rotating in the same circle for prolonged periods of time, bearing and dealing with a great deal of pain and suffering. Unfortunately, some Palestinian cancer patients died while waiting for Israeli permits, to obtain new hospital appointments, and then to enter East Jerusalem’s hospitals for treatment.

Another crucial issue affecting Palestinian cancer patients in the Occupied Palestinian Territories is corruption. Corrupt behaviors by some official institutions of the Palestinian Authority, dealing with cancer patients, have resulted in extraordinary suffering for cancer patients, and even their death in some cases, as happened in the case of the 16-year old boy – Saleem Nawati – from Gaza. Corruption in the case of “Khaled Al-Hassan Cancer Hospital and Bone Marrow Transplant Project” (KAHHP), in Surda town near Ramallah, occupied West Bank, was and is still a major “cancerous” scandal for the Palestinian Authority, its government, and associated ministries and institutions. Donations of about USD 13.5 million raised for the project – KAHHP – had evaporated. Although it has been more than 7 years since the project was launched in 2016, no one knows where the money, raised from people’s donations and cut from employees’ salaries, had gone. Accordingly, based on thorough and transparent investigations, penalties should be enforced on those who are/ were, directly or indirectly, involved, with respect to the failed, hypothetical, and scandalous “Khaled Al-Hassan Cancer Hospital and Bone Marrow Transplant Project”.

In light of the many difficulties, problems, limitations, and challenges, as well as corruption events, investigated and discussed in this research paper, it is recommended that serious and honest steps should be taken to reduce the suffering of Palestinian cancer patients in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, with priority given to ending the Israeli military occupation that began in June 1967. More generous funds are also needed to improve the healthcare system for the Palestinian cancer patients.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: This paper was not published before and is not considered for publication anywhere else. No individual participants or material were involved in this study and, thus, there is no need to obtain informed consent.

Consent for publication: All material presented herein does not need consent to publish.

Availability of data and materials: All the data and material used to serve the purpose of this research work are provided in the paper.

Competing interests: There is no potential of conflict of interest of any kind (financial or otherwise).

Funding: The research presented herein did not receive any funding from any individuals or organizations.

Authors’ contributions: This research paper has been authored by the author alone, as single author.

Acknowledgements: The author expresses his sincere thanks to friends and colleagues who critically reviewed the paper. He also extends his great appreciation to the Journal – Med Discoveries – and its Editorial Team, especially Ms. Kathryn Campbell for her great assistance during the production stage of the paper.

References

Note: If the links of some of the references used do not open when clicking on them, please copy those links and paste them in your browser to open.

- Hansen LA. Convenience, challenges, and cost containment: The impact of specialty pharmacies on patient care. TOP Oncol Pharm. 2012. https://www.theoncologypharmacist.com/topissues/issue-archive/14797-top-14797

- Seiler A, Jenewein J. Resilience in cancer patients. Front Psychiatry. 2019. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00208 https:// www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00208/full

- Lou E, Teoh D, Brown K, Blaes A, Holtan SG, Jewett P, et al. Perspectives of cancer patients and their health during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE. 2020; 15(10): e0241741. h t t p s : / / d o i . o r g / 1 0 . 1 3 7 1 / j o u r n a l . p o n e . 0 2 4 1 7 4 1 https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal. pone.0241741

- Mitra M, Basu M. A study on challenges to health care delivery faced by cancer patients in India during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Prim Care Community Health. 2020; 11: 2150132720942705. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7448263/

- Lewandowska A, Rudzki G, Lewandowski T, Rudzki S. The problems and needs of patients diagnosed with cancer and their caregivers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021; 18(1): 87. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7795845/

- Peikert ML, Inhestern L, Krauth KA, Escherich G, Rutkowski S, Kandels D, et al. Fear of progression in parents of childhood cancer survivors: Prevalence and associated factors. J Cancer Surviv. 2022; 16: 823-833. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-021- 01076-w https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11764- 021-01076-w#citeas

- Worldometer. State of Palestine Population Live: 5,399,777, as of January 13, 2023. https://www.worldometers.info/worldpopulation/state-of-palestine-population/#:~:text=The%20current%20population%20of%20the,the%20latest%20United%20 Nations%20data

- AlWaheidi S, Sullivan R, Davies EA. Additional challenges faced by cancer patients in Gaza due to COVID-19. Ecancer. 2020;14: ed100. https://doi.org/10.3332/ecancer.2020.ed100 https:// ecancer.org/en/journal/editorial/100-additional-challengesfaced-by-cancer-patients-in-gaza-due-to-covid-19

- Halahleh K, Abu-Rmeileh NME, Abusrour MM. General oncology care in Palestine. In: Al-Shamsi HO, Abu-Gheida IH, Iqbal F, AlAwadhi A (Eds.): Cancer in the Arab World. Springer, Singapore. 2022; 13: 196-213. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-7945- 2_13

- Salem HS. Cancer status in the Occupied Palestinian Territories: types; incidence; mortality; sex, age, and geography distribution; and possible causes. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-022-04430-2 https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00432-022-04430-2 https://www.researchgate. net/publication/364342942_Cancer_Status_in_the_Occupied_ Palestinian_Territories_Types_Incidence_Mortality_Sex_Age_ and_Geography_Distribution_and_Possible_Causes

- WHO (World Health Organization). Gaza Strip and West Bank Source: Globocan 2020. International Agency for Research on Cancer. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland. 2020. https://gco.iarc.fr/ today/data/factsheets/populations/275-gaza-strip-and-westbank-fact-sheets.pdf

- Das M. Cancer care crisis in the Palestinian territories. LANCET Oncol. 2022; 23(5): 575. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470- 2045(22)00218-2

- Knell Y. The Palestinian cancer centre that can’t take patients. British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC News). 2022. https:// www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-60829319

- OCHA (Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian .Affairs, UN) Escalation in the Gaza Strip and Israel | Flash as of 18:00, August 8, 2022 https://www.ochaopt.org/content/escalation-gazastrip-and-israel-flash-update-2-august-2022

- Wikipedia. Gaza–Israel conflict. 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/ wiki/Gaza%E2%80%93Israel_conflict

- Wikipedia. Augusta Victoria Hospital. 2022. https://en.wikipedia. org/wiki/Augusta_Victoria_Hospital

- LWF (The Lutheran World Federation). Jerusalem: US President Biden visits Augusta Victoria Hospital East Jerusalem, Palestine/ Geneva. 2022. https://www.lutheranworld.org/news/jerusalem-us-president-biden-visits-augusta-victoria-hospital

- LWF (Lutheran World Federation). “Restore hope, revive dreams.” New unit for bone marrow transplantation at AugustaVictoria-Hospital. 2016. https://jerusalem.lutheranworld.org/ content/restore-hope-revive-dreams-131

- OCHA (Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, UN). Additional treatment option available to cancer patients in Gaza amid tightening of access limitations. The Humanitarian Bulletin, March–May 2020, Contributed by the World Health Organization (WHO). 2020. https://www.ochaopt.org/ content/additional-treatment-option-available-cancer-patientsgaza-amid-tightening-access

- EEAS (European External Action Service). EU renews its support for the Palestinian people with a €224.8 million assistance package. 2022. https://www.eeas.europa.eu/delegations/palestineoccupied-palestinian-territory-west-bank-and-gaza-strip/eurenews-its-support_en?s=206#:~:text=Today%2C%20the%20 European%20Commission%20has,in%20the%20occupied%20 Palestinian%20territory

- Vanona D. Augusta Victoria Hospital denies care to Palestinian cancer patients. iGlobenews Community. 2022. https://www. iglobenews.org/augusta-victoria-hospital-denies-care-to-palestinian-cancer-patients/

- UN News. UN-sponsored, Italian-financed cancer centre opens in West Bank. 2003. https://news.un.org/en/story/2003/05/68952-un-sponsoreditalian-financed-cancer-centre-opens-west-bank

- ANERA (American Near East Refugee Aid). Bethlehem is home to two UNESCO World Heritage sites, including the ancient senasil, or stone-walled terraces, Bethlehem Governorate. 2022. https://www.anera.org/stories/bethlehem-palestine/

- WAFA News (2020). Hebron Governmental Hospital begins receiving cancer patients from the Governorate’s residents who were seeking treatment in Bethlehem, as a precaution against the Coronavirus. 2020. YouTube (in Arabic) March 15, 2020. https://fb.watch/gTJ1NtDtVk/

- Al-Rabi’a Radio Station. What is the reason that prompted [Palestinian] cancer patients to say that they were sentenced to “death”? A 2.38 minutes’ YouTube video (in Arabic), Hebron, Occupied West Bank, Palestine. 2022.

- PCRF (Palestine’s Children’s Relief Fund). Our pediatric cancer departments. Treating kids with cancer in Palestine. The PCRF is the main nonprofit in the world building up cancer services for children in the Middle East. 2022. https://www.pcrf.net/pages/ pediatric-cancer-departments

- UP (Ultra Palestine). Beit Jala: Dissatisfaction with the transfer of cancer treatment: “We waited for a hospital to be prepared, so we were transferred to a room.” (A Report in Arabic). 2022. https://ultrapal.ultrasawt.com/%D8%A8%D9%8A%D8%AA- % D 8 % A C % D 8 % A 7 % D 9 % 8 4 % D 8 % A 7 - % D 8 % A 7 % D 8 % B 3 % D 8 % A A % D 9 % 8 A % D 8 % A 7 % D 8 % A 1 - % D 9 % 8 5 % D 9 % 8 6 - % D 9 % 8 6 % D 9 % 8 2 % D 9 % 8 4 - % D 8 % B 9 % D 9 % 8 4 % D 8 % A 7 % D 8 % A C - % D 9 - % 8 5 % D 8 % B 1 % D 8 % B 6 % D 9 % 8 9 - % D 8 % A 7 % D 9 % 8 4 % D 8 % B 3 % D 8 % B 1 % D 8 % B 7 % D 8 % A 7 % D 9 % 8 6 - % D 8 % A 7 % D 9 % 8 6 % D 8 % A A % D 8 % B 8 % D 8 % B 1 % D 9 % 8 6 % D 8 % A 7 - %D8%AA%D8%AC%D9%87%D9%8A%D8%B2-%D9%85%D8%B3%D8%AA%D8%B4%D9%81%D9%89-%D9%81%D9%86%D9% 8F%D9%82%D9%84%D9%86%D8%A7-%D9%84%D8%BA%D8% B1%D9%81%D8%A9/%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AA%D8%B1%D8 %A7-%D9%81%D9%84%D8%B3%D8%B7%D9%8A%D9%86/%D 9%85%D8%AC%D8%AA%D9%85%D8%B9

- PCHR (Palestinian Centre for Human Rights). The situation of cancer patients in the Gaza Strip: Report on travel limitations for cancer patients under the state of emergency and dissolution of agreements with the Israeli occupation authorities. 2020. https://www.pchrgaza.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/ Cancer-booklet-2020-English-Print.pdf

- Ramahi S. Corruption in the Palestinian Authority. Special Report. Middle East Monitor (MEM), London, UK. 2013. https:// www.aman-palestine.org/cached_uploads/download/migrated-files/itemfiles/b2a7e241322895ba53fdd6425a55c40a.pdf

- Fatafta M. Neopatrimonialism, corruption, and the Palestinian Authority: Pathways to real reform. Al-Shabaka: The Palestinian Policy Network. 2018. https://al-shabaka.org/circles/neopatrimonialism-corruption-and-the-palestinian-authority-pathwaysto-real-reform/

- Magd, Lh. To cut corruption in the Palestinian Authority, cut off development aid. GAB | The Global Anticorruption Blog: Law, Social Science, and Policy. 2021. https://globalanticorruptionblog.com/2021/07/26/to-cut-corruption-in-the-palestinian-authority-cut-off-development-aid/

- Abu Toameh K. Majority of Palestinians believe corruption increased, poll finds. The results showed that widespread corruption poses the most important challenge to the Palestinians, followed by the “occupation,” economic issues, and the dispute between the PA and Hamas. The Jerusalem Post. 2021. https:// www.jpost.com/middle-east/majority-of-palestinians-believecorruption-increased-poll-finds-688766

- Muaddi Q. Corruption is the main concern for Palestinians, says local anti-corruption watchdog. The New Arab. 2022. https:// english.alaraby.co.uk/news/corruption-leading-concern-palestinians-says-watchdog

- WAFA. Anti-Corruption Authority: 82 cases of corruption were submitted to the Corruption Crimes Court. WAFA News Agency 2022. https://english.wafa.ps/Pages/Details/128982

- Salem HS. Digitization of the health and education sectors in the Palestinian society, in view of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. In: Brauweiler H-C, Kurchenkov VV, Abilov S, Zirkler B. (Eds.): “Digitalization and Industry 4.0: Economic and Societal Development – An International and Interdisciplinary Exchange of Views and Ideas.” 2020; 53—89. https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783658271091 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336813269_Digitization_of_the_Health_and_Education_Sectors_in_the_Palestinian_Society_in_View_of_the_United_Nations_Sustainable_ Development_Goals_Book_Chapter_Springer_Germany

- Brown NJ. Time to rethink, but not abandon, international aid to Palestinians. Carnegie Foundation for International Peace. 2018. https://carnegieendowment.org/2018/12/17/time-to-rethinkbut-not-abandon-international-aid-to-palestinians-pub-77985

- UN (United Nations). The Question of Palestine – United Nations Office of the Special Coordinator in the Occupied Territories: Rule of Law Development in the West Bank and Gaza Strip Survey and State of the Development Effort – May 1999. Rule of Law Development in the West Bank & Gaza Strip – UNSCO Survey. 1999. https://www.un.org/unispal/document/auto-insert-206942/

- RAND Corporation. About the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA, USA. 2022. https://www.rand.org/about.html

- RAND Corporation. Building a Successful Palestinian State. The RAND Palestinian State Study Team. RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA, USA. 2005. https://www.un.org/unispal/wp-content/uploads/2005/04/26808aa58709c22385256ff1004ebb eb_Building%20a%20Successful.pdf

- Rose D. Ghost hospitals reveal corruption in Palestinian Authority health sector. Special Report: Britain blew £200m on West Bank healthcare since 2008. The JC. 2022. https://www.thejc. com/news/world/ghost-hospitals-reveal-corruption-in-palestinian-authority-health-sector-2SAYUsuTUV4hTYSJ9EdhvY

- Ibrahim N. Teen’s death fuels Palestinian Authority corruption claims. The PA [Palestinian Authority] is accused of nepotism over the death of a 16-year-old cancer patient Saleem Nawati after he was denied treatment in West Bank. Aljazeera. 2022. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/2/8/teens-death-fuelspalestinian-authority-corruption-claims

- PECDAR (Palestinian Economic Council for Development and Reconstruction. Khaled Al-Hassan Hospital for Cancer and Bone Marrow Transplant Project (An article in Arabic). 2022. http://www.pecdar.ps/article/1147/%D9%85%D8%B4%D8 %B1%D9%88%D8%B9-%D9%85%D8%B1%D9%83%D8%B2- % D 8 % A E % D 8 % A 7 % D 9 % 8 4 % D 8 % A F - % D 8 % A 7 % D 9 % 8 4 % D 8 % A D % D 8 % B 3 % D 9 % 8 6 - %D9%84%D9%84%D8%B3%D8%B1%D8%B7%D8%A7%D9%86- %D9%88%D8%B2%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%B9%D8%A9-%D8%A7 %D9%84%D9%86%D8%AE%D8%A7%D8%B9

- Daralomram. Khaled Al Hasan Cancer Center. 2017. https://www.daralomran.com/2017f.html

- Bedounraqaba.net. Khaled Al-Hassan Hospital in Ramallah... Millions [of dollars] have been collected and the result is zero! (An article in Arabic). 2022. https://bedounraqaba.net/%D9%85%D8%B3%D8%AA%D8 %B4%D9%81%D9%89-%D8%AE%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AF- % D 8 % A 7 % D 9 % 8 4 % D 8 % A D % D 8 % B 3 % D 9 % 8 6 - % D 9 % 8 1 % D 9 % 8 A - % D 8 % B 1 % D 8 % A 7 % D 9 % 8 5 - %D8%A7%D9%84%D9%84%D9%87-%D9%85%D9%84%D8%A7 %D9%8A%D9%8A%D9%86-%D8%AC/

- Shehab News. Questions about the “Khaled Al-Hassan” Hospital for Cancer Treatment, only excavations were found! (An article in Arabic). 2022. https://shehabnews.com/p/94441

- Shahed. To reveal the funds of Khaled Al-Hassan Hospital, the People’s Alliance threatens the Palestinian Authority to take to the street (An article in Arabic). 2022. https://shahed.cc/news/6562

- WAFA. Donations collected for the establishment of a cancer center are available but not enough to launch the project – MoH. 2022. https://english.wafa.ps/Pages/Details/127661

- PEP (Palestine Economy Portal). Khaled Al-Hassan Cancer Treatment Center: An urgently needed project, with an overall cost of $250 M. 2016. https://www.palestineeconomy.ps/en/Article/287/Khaled-Al-Hassan-Cancer-Treatment-Center-an-Urgently-Needed-Project,-with-an-Overall-Cost-of-250-M

- AMAN. Findings of the Commission of Inquiry into the death of Saleem al-Nawati, a child, are a good step towards promoting accountability and require a serious follow-up. Need to move forward with improving the public health system, notably a comprehensive and binding health insurance. AMAN Transparency, Ramallah, Palestine. 2022. https://www.aman-palestine. org/en/activities/16541.html

- Darik News USA. Kishor’s death fuels Palestinian Authority’s claims of corruption. Authorized West Bank News. 2022. https://darik.news/usa/world/kishors-death-fuels-palestinianauthoritys-claims-of-corruption-authorized-west-bank-news. html